Female genital mutilation is the practice of removing one or more parts of the external female genital organ for cultural, religious and folk beliefs and not for medical reasons. It is performed on girls between the ages of thirteen and fifteen on average, but in some cases from the age of five to newborns. FGM, crude to make it better understood, is often performed with spartan and rudimentary instruments and in inadequate hygienic conditions. And it is considered a violation of human rights.

Some reasons for the mutilation.

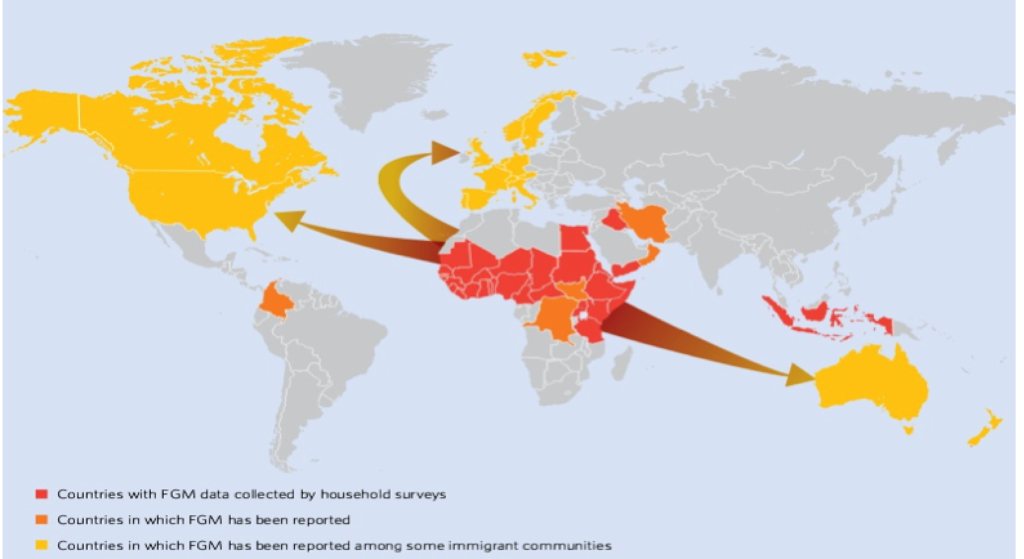

The origin of this custom has been lost in time; in fact, it is said that even before the birth of the major religions, FGM was already practised. The spread basically started on the African continent and then spread to other parts of the world as a result of migrations.

It is therefore difficult to relate the fact to a precise reason. A first reason is given by a question related to the growth of women in society: this is thought to constitute the transition from puerile age to adulthood. It prepares the person for grief, for the possibility of being able to marry, and consequently to be able to demand a larger dowry from the family of origin. In addition to this, aesthetic or allegedly hygienic reasons intervene: the female external organ, after mutilation, would become less ugly and less dirty and consequently more suitable to be desired and have better functionality during gestation and childbirth. And again, it is believed, in this way, to guarantee greater security for the woman who will be less likely to be raped. Lastly, the practice of FGM will guarantee the husband more fidelity from his wife. The task of performing this type of operation is often given to specialised and, moreover, well-paid women.

Types of female genital mutilation.

Female genital mutilation is practised in different ways depending on the situation. Quoting the World Health Organisation directly, there are four types of FGM with about six subcategories attached:

- Type I (Sunna): consists of the partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or its foreskin;

- Type I a: consists in the removal of the foreskin/clitoral hood (circumcision);

- Type I b: consists in the removal of the clitoris together with the foreskin (clitoridectomy);

- Type II: consists in the partial or total removal of the clitoris and labia minora, with or without the removal of the labia majora (excision or excision);

- Type II a: consists in the removal of the labia minora only;

- Type II b: consists in the partial or total removal of the clitoris and labia minora;

- Type II c: consists in the partial or total removal of the clitoris, labia minora and labia majora;

- Type III (Pharaonic Circumcision): consists in the narrowing of the vaginal orifice with the creation of a closure by cutting and repositioning the labia minora or labia majora, with or without the removal of the clitoris. In many cases the skin flaps of the labia are sewn together (infibulation). This procedure often requires an additional practice of reopening the stitched suture, with the aim of facilitating sexual intercourse and/or childbirth. Often, women are infibulated and de-infibulated several times throughout their lives experiencing unimaginable suffering;

- Type III a: consists in the removal and apposition of the labia minora with or without excision of the clitoris;

- Type III b: consists in the removal and apposition of the labia majora with or without excision of the clitoris;

- Type IV: are all other practices considered harmful to the female genitals and performed for non-therapeutic reasons. They include puncturing, piercing, incising, scraping or cauterising the clitoris, cutting the vagina (gishiri) or introducing corrosive substances into the vagina to shrink it or make it dry.

Consequences of female genital mutilation.

Obviously, the consequences for all girls or women who undergo this practice are frightening. Firstly, these operations take place under very poor hygienic conditions, making infections very likely. The pain experienced is excruciating and the loss of blood is another danger factor. This is followed by consequences that the victims will carry with them for the rest of their lives: psychological problems, difficulty urinating, infertility problems, complications during gestation and childbirth, and an increased propensity for the infant to die. And logically a partial or total loss of sexual pleasure.

How to fight FGM

The primary tool for combating female genital mutilation is culture. Firstly, the awareness that every woman must have concerning her rights, and secondly, the responsibility that states and societies have towards their members. Female schooling, which precisely after FGM is interrupted, should continue in such a way as to give the possibility of a conscious choice with respect to all the customs and impositions that the social fabric places on women themselves. At the same time, we are fortunately moving in the direction of making mutilation illegal. Several countries have in fact banned this practice. The difficulty lies in reaching all those micro communities where it is still considered essential to carry on this custom to preserve the identity of the community itself. At the international level, thanks to the CEDAW (Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women), very important steps forward have been taken. Quoting Article 1 of the convention reads:

Any distinction, exclusion or limitation based on sex, which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women, irrespective of their marital status and under conditions of equality between men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil, or any other field.

It is very important to remember that the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation has been established on 6 February each year and that the World Health Organisation has included the elimination of FGM among the Sustainable Development Goals to be achieved by 2030.