It’s dinnertime and you open the fridge for inspiration. There is nothing exciting you, so you decide to order something. You might try a new restaurant or call that place that never disappoints. This sounds a great plan. However, this scenario is foreign to millions of people around the world. Can you imagine opening your cupboard and finding absolutely nothing to eat? Even a loaf of stale bread to stave off hunger. These are two completely different realities under the same premise: ‘There is nothing to eat’.

The campaign of Banco de Alimentos Perú (BAP), launched in July this year to raise awareness of the difficult reality faced by millions of Peruvians, presents us a powerful perspective. Here, two people utter the same phrase, but their completely different economic situations give rise to strikingly different meanings. One expresses her discontent at being unable to find a food she likes, while the other reveals, literally, her lack of food.

So why is this commercial particularly important? Because the context behind it reflects a serious global problem.

Food uncertainty

According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), food uncertainty is defined as the lack of regular access to sufficient nutritious food for normal and healthy development. This situation may be caused by a shortage of food in a given location or due to a lack of resources to obtain it.

Therefore, with uncertain access to food, there is a high chance that people will be forced to sacrifice other basic needs just to be able to get something to eat. In addition, economic limitations force them to opt for what they can get most easily and cheaply, which often means food that is low in nutrients. This leads to long-term health problems.

The main effects: malnutrition and obesity. Two diseases that coexist in many countries and can be a direct consequence of food insecurity. In addition, there are other forms of malnutrition, such as anaemia, as well as the risk of developing chronic diseases, such as diabetes, especially if children are facing this deficiency.

COVID-19’s impact

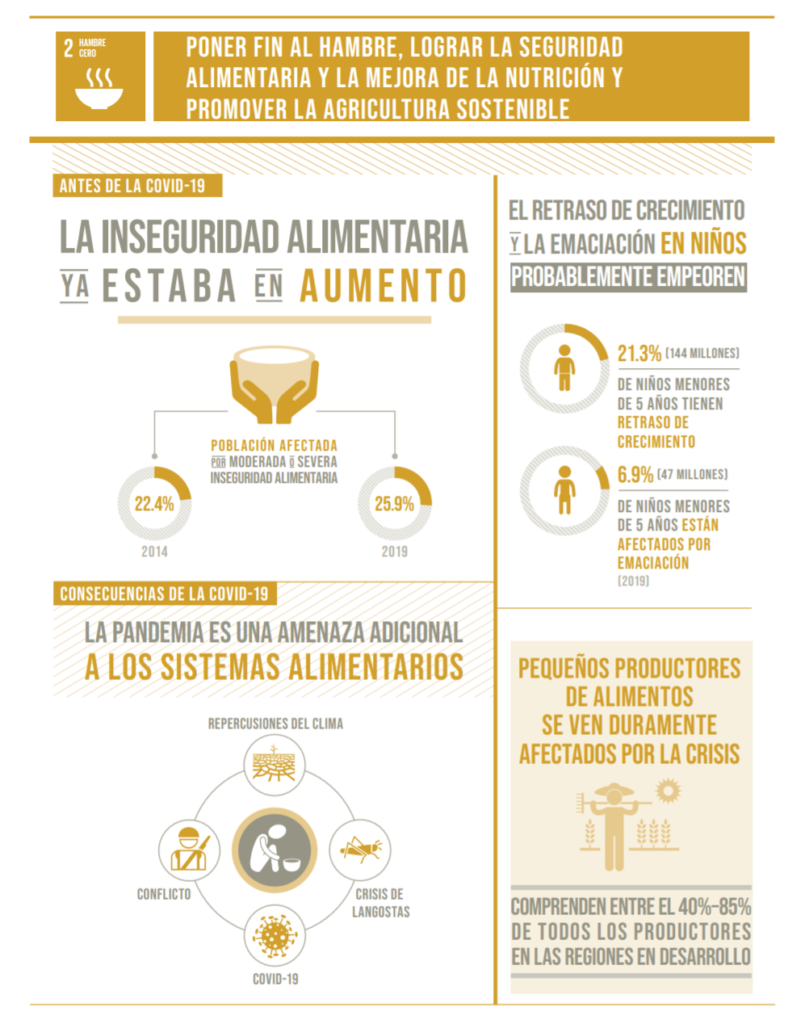

In 2015, the year in which the UN established the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), malnutrition and famine were already worrying problems for the UN, but by 2023 (the latest study published) the situation had become alarming.

The prevalence of food insecurity, moderate or severe, continues to be significantly above pre-pandemic levels. In 2023, 28.9% of the world’s population was estimated to be food insecure, equivalent to about 2.33 billion people – more than a third of the world’s population!

COVID-19 has aggravated this crisis, by increasing food insecurity around the world. Credits: https://sdgs.un.org/es

This figure doubled in Peru, so that by 2022, the FAO considered it the most food insecure country in South America. With more than half of the population affected, the levels of anaemia and obesity it faces have also increased significantly.

The increase of poverty, aggravated by the global fuel crisis and fertiliser shortages, affected terribly a population that is still not recovering from the ravages of the pandemic. Uncontrolled food price inflation, exacerbated by the dramatic effects of climate change on agriculture, has made healthy food almost impossible to access for more than half of the country. This diet would cost a minimum of $3.50 a day.

The Bank of Peru

The Banco de Alimentos Perú (BAP) is an organisation with a tough fight ahead of it, with more than 16.6 million Peruvians facing food insecurity.

This bank, founded in 2014 and endorsed by The Global FoodBanking Network, is aware that, although Peru eats well, there are also many families who do not have access to their daily food. In fact, they indicate that, out of every 10 Peruvians, 6 have spent at least one day without food.

Therefore, the mission of this organisation is to combat hunger and food waste in the country. They mediate between companies that have products with short expiry dates, overproduction or packaging failures, and vulnerable populations. By doing so, they recycle food that no longer has commercial value but is safe for human consumption and meets high quality standards. Currently, they have brought aid to 19 regions of the country.

In addition, the BAP conducts various activities to raise funds and awareness of the adversities their compatriots face. A donation, as they say, can make the difference in a critical situation, determining whether to eat or not to eat.

Food waste

Hunger and waste. Two opposites that intersect to form a tragic paradox.

According to the BAP, 9 million tonnes of food are wasted in Peru every year. Globally, this figure amounts to 1050 million tonnes according to UN data. In other words, that would be about 132kg per person or about 1 billion plates of food per day. This is while one third of humanity is food insecure.

Food waste is a global drama. Millions of people starve today because of food waste around the world”-Inger Andersen, executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

One fifth of all food available for human consumption is wasted. Of this total, 60% of waste comes from domestic households, 28% from food service providers and the remaining 12% from the retail trade. We are all responsible.

The figures continue: this waste generates between 8 and 10% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, a cost equivalent to a trillion dollars for the global economy and a significant loss of biodiversity by occupying an area similar to almost a third of the world’s agricultural land. These are extremely worrying data that show us the reality behind the food we harvest, but do not consume. It is not for nothing that one of the SDG objectives is to halve food waste by 2030. At the moment, the road still seems far from over.

Most food waste occurs in household consumption, which highlights the importance of reducing waste in our homes.

At least I hope that the next time you open your fridge and find something to eat, you know how lucky you are and do not let your food go to waste.

You may be interested in: Will the kitchen of the future be marked by a green approach?