The regularisation of factories is presented as a transformation programme with many ideas and initiatives, but what exactly does it consist of, and what pioneering projects has it so far given rise to?

Factory regularisation: a more ethical and environmental perspective

It has not only increased clothing and the prestige of fashion by millions; it has also boosted employment and the global economy. We are talking about the textile sector, of course, one of the world’s leading financial banks. However, despite its positive contribution, there is no denying the negative impact of this sector on the environment, which is responsible for much of the industrial pollution that is currently suffocating the planet.

Yes, the textile and fashion world has its dark, horrible and reproachful side. And its anti-ecological stain is not (and has not been) the least of its grievances. Clandestine workshops, exploited workers, vulnerable labour, flouted labour inspections, precarious sanitary conditions, alarming legal infractions… etc. And all in the name of saving on production costs.

And it is precisely in this context that the urgent and pressing need to implement a regularisation of garment factories arises. In other words? To put in place viable and effective measures to control textile production, this time with a much more ethical and much more environmental approach.

Did you know that textile production is the second most polluting in the world?

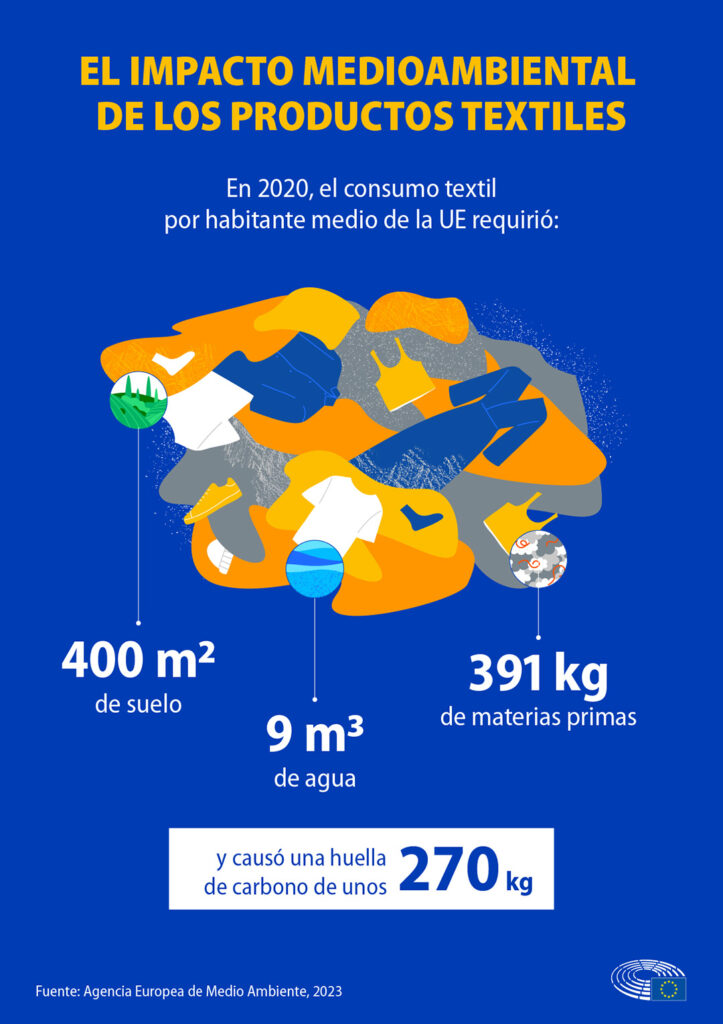

That the fashion business leaves a catastrophic footprint on the environment is an open secret. It is no coincidence that between 3% and 10% of carbon emissions, no less, are attributed to this activity, and that at a global level. The Carbon Trust, a British consultancy firm, has reported, affirmed and denounced this in its 2020 report on the environmental consequences of fashion weeks.

What is the reason for this? Basically, because of its priority mode of transport. Air travel, in essence, is responsible for leaving behind 2 to 3% of the world’s CO2 footprint. But the impact of textile manufacturing goes beyond even its carbon footprint. Excessive water consumption has turned this business into an enemy of natural resources. An enmity reaffirmed by its tendency to pollute rivers and lakes, by the way, as well as using the most toxic chemicals.

In fact, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, the textile sector generates 1.2 billion tonnes of CO₂ per year, more or less. That is 10% of global emissions. Estimates to which must be added the 500,000 tonnes of microfibres that are dumped into the ocean (every year), derived in turn from the washing of synthetic textiles. This is marine pollution that is impossible to ignore.

These alarming figures have fortunately helped to raise social and environmental awareness about textile production, its impact and the way and pace at which clothes are consumed. This in turn has helped to fuel a very topical movement for sustainable change. The regulation of textile factories is therefore seen as a possible ecological solution. In what sense? By promoting sustainability on the one hand, without losing sight of respect for human rights on the other.

Regularisation of factories: from transparency of supply to tightening of laws

Ensuring transparency in each of the links that make up the textile supply chain is undoubtedly one of the first measures to be taken. And why? Because many brands subcontract their production, delegating this task to factories that operate in unethical conditions.

We are talking about jobs where labour exploitation, firstly, and the environmental impact, secondly, is very high. This is why the commitment to systems that require companies to provide detailed information on where and how their products are manufactured is a priority and essential in this campaign and fight. Especially as traceability can help identify and eliminate worker exploitation, pollution and other harmful practices.

In this sense, it can be said that certification seals play a crucial role. Their task is to assure the buyer that the factories of the brand of the garment he or she is about to purchase comply with both ethical standards and environmental requirements.

On the other hand, there is no doubt that the regularisation of factories also involves tightening the carbon emissions of textile companies. We are talking about setting limits, yes. Limits set by governmental and international authorities. Barriers that set lower emission rates, look at wastewater treatment, and even require them to invest in cleaner technologies. In other words?

Wield legislation to encourage companies to develop more sustainable processes, especially in regions where textile production is particularly high. Starting with the use of renewable energies, for example, and continuing with water recycling, for example. Not to mention implementing more rigorous policies that monitor the use of toxic chemicals, and even control waste management.

It is no less important to put an end to linear consumption and to promote the circular economy. Continuous reuse and recycling of resources is another measure in favour of the regularisation of textile factories. The important thing at this point is to leave behind the consumerist model where clothes are first manufactured, then consumed, then finally discarded. The answer to this?

To encourage the creation of products from materials that have already been recycled. But also to reduce the demand for virgin resources, to advocate the use of reusable fibres, and to promote second-hand clothing collections.

Regulating factories must not neglect the ethical approach

A term that, in terms of business, should translate into promoting and respecting fair and dignified working conditions. And as a line to follow, those outlined by the ILO or International Labour Organisation.

It is worth remembering at this point that many of those who work in these textile jobs do so in dangerous conditions. Not to mention their long and exhausting working hours, all for low pay. Clothing brands must therefore ensure and take responsibility for ensuring that their suppliers and factories comply with international labour standards. One way to make sure that these standards are actually obeyed?

Conducting independent labour audits, for example. Transparent and public audits, moreover. The measure would essentially allow consumers to have more information about the brands they plan to buy and, on that basis, to make a decision accordingly.

Proof of the importance of keeping consumers well informed is the fact that some brands have already started to use green labels. Informative and clear labels that also detail the ecological footprint of each garment. A measure to regulate factories that can have an even greater effect as consumers become more educated and aware.

Because it is indisputable that when consumers demand certain types of products, brands are forced to adapt to these demands. A buying and selling requirement that can play in favour of the transformation of this industry, inducing it to move towards a more sustainable and ethical model. The question, at this point, is whether it is possible to push consumers towards textile sustainability.

The answer is a resounding yes. How? By resorting to the old trick of awareness-raising campaigns. Strategies that teach consumers about the environmental and social impact of the clothes they buy.

Finally, government incentives and tax policies are also an interesting way to encourage the regularisation of factories. In short, it is a matter of rewarding textile companies that adopt and implement sustainable patterns, either with subsidies or tax reductions. This economic and political recognition could also be given to factories that improve the working conditions of their employees, or to those that invest in clean technologies.

On the other hand, it would not be unreasonable to punish companies that do not comply with the standard through taxation. Translation? Fiscal policies that discourage unsustainable production. How, exactly? By imposing environmental taxes, basically. Punishing factories that exceed the carbon emissions limit, or generate large amounts of waste.

A database for supply chains, the new sustainable face of textiles

A peace offering, a green and ecological leaf. This is the essence of the latest idea of the prefecture of Milan, published a few weeks ago by BoF , after proposing to launch a database on the supply chain in the Lombard capital. The measure makes no secret of it: protecting ‘Made in Italy’ is its priority goal; and if it has to monitor Italian production more closely to do so, so be it.

According to the breakdown of its details, this measure to regularise factories would only apply to the Lombardy region, for the time being. Its modus operandi, in any case, is none other than to create a centralised platform to help and guide producers.

A database that would also make it possible to upload and download all the documents necessary to certify the legality of the workplaces. A scheme of action that, in short, could encourage the regularisation of factories, yes. The same goes for brands and authorities, especially those in charge of carrying out inspections.

For many leaders involved in this project, implementing this database could be the solution to a problem that has been affecting the entire national productive sector for years. The task is complex, it is true. But bringing together in a single access point all the documents and personal information of Lombardy’s factories could well go beyond being a simple initiative still under discussion and become an example of innovation.

Regularisation of the factories: because it is no longer a question of making more, but of making better

In short, the world of clothing is starting to show that it can be positive, in terms of sustainability. From design and choice of materials, to consumer involvement and working conditions, to strategic direction and fashion show production. Branches and sections that are increasingly opting to achieve the usual goals, and not always in the most traditional and polluting way.

Yes, the control of production and the regularisation of textile factories is essential if we really want to reduce the impact of this industry on the planet. An ethical and environmental approach that can in turn improve the working conditions of millions of workers around the world.

All it takes is for government intervention to be allied with consumer support to begin to transform the textile industry into a better force. An alliance that, if well managed, could promote social justice while protecting the environment. Progress, however, lies with consumers, who have the power to make a difference. How? By demanding more environmentally friendly products, yes; and by consuming truly green practices and initiatives.

For what is important, in this struggle to establish better regulation of factories, is to pay tribute and homage to human rights and environmental justice. Making another bow, of recognition and awareness, to craftsmanship and innovation, circular economy and inclusion.