Do you know what rezoning is and how it affects biodiversity? Come in and find out how rezoning can be a slap in the face for the conservation of natural resources.

It is both useful and contentious, a challenge and a danger. Rezoning poses many challenges and benefits, an invitation for cities to grow and strengthen. But as is well known, all that glitters is not gold. So it is time to look at the downsides of this process; and this time from an environmental perspective.

What is rezoning?

It is, quite simply, an urban planning intervention applied by the authorities; no more than that. Strictly and in official terms, rezoning is nothing more than the legal process by which a piece of land changes its designation and zoning. Translation? It is the legitimate ruling in which the same land is allowed to have a different use.

Thus, land that was previously zoned residential, for example, may be converted to commercial or even industrial use, for example. It is therefore very common to see that the existing zoning category of a piece of land undergoes a modification after rezoning. Yes, indeed, to allow for a different type of employment. It is basically, in a nutshell, a full-blown reuse.

Figures such as Patrick Condon, a planner and professor at the University of British Columbia, argue that rezoning contributes to increasing the price of land. In what way? Because it increases the desirability and skyrockets the value of development. Or so he argued at a 2021 conference on California’s livability. Urban planner Wendell Cox, for his part, points out that rezoning is a redesign of land, and that it influences housing affordability.

In any case, for all urban planning critics in general, and for both experts in particular, a good and true rezoning has to meet certain regulatory guidelines. The most important one? Specifying the type of building permit reserved for such land. And that is exactly why factors such as population density, building heights, setbacks, impact, compatibility with the environment, etc., must be detailed.

Yes, there is no doubt that rezoning has its good things; or interesting things, at least. And one of them is being able to respond to market demand. A growing city tends to demand more commercial space, not to mention more residential areas. And that is where this sort of land ‘redevelopment’ comes into play: allowing existing land to be reused to respond to new needs.

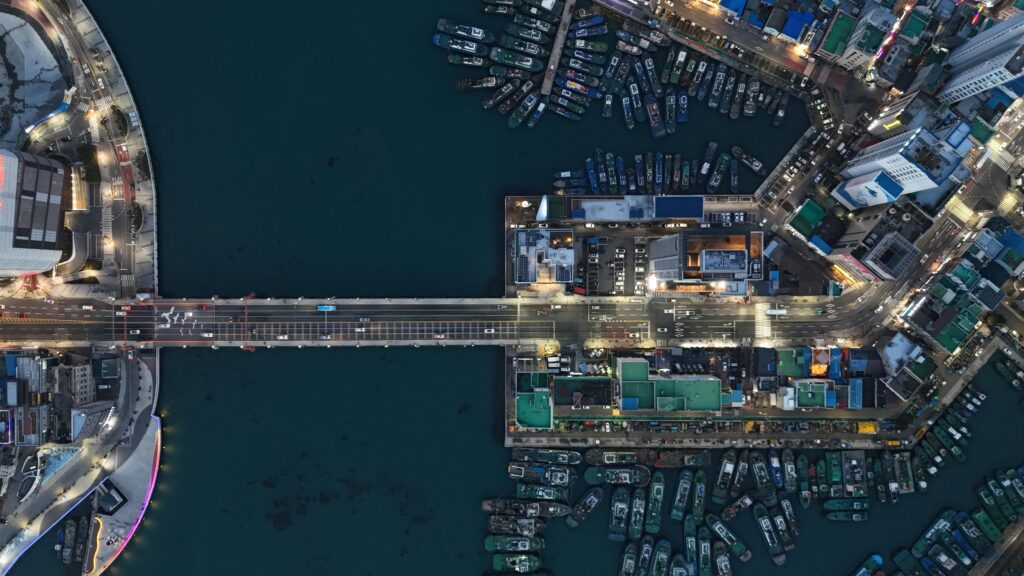

In this way, this strategy of ‘recycling’ and ‘density’ becomes synonymous with economic development. And its effectiveness is clearly seen in cities that redevelop their land to attract businesses and thus create jobs, boosting the local economy in the process. Growth that, in turn, opens the door to a variety of infrastructure changes, from road projects to generating transport and public services.

But the problem with rezoning arises when the environmental impact of the new land use is weighed against the environmental impact. This is because the effects of rezoning on wildlife, water resources, natural parks and green spaces are often not considered. We are referring, indeed, to the transformation of rural land into urban land; and the modification of ecosystems; and the reduction of green spaces… and that’s just to name a few consequences.

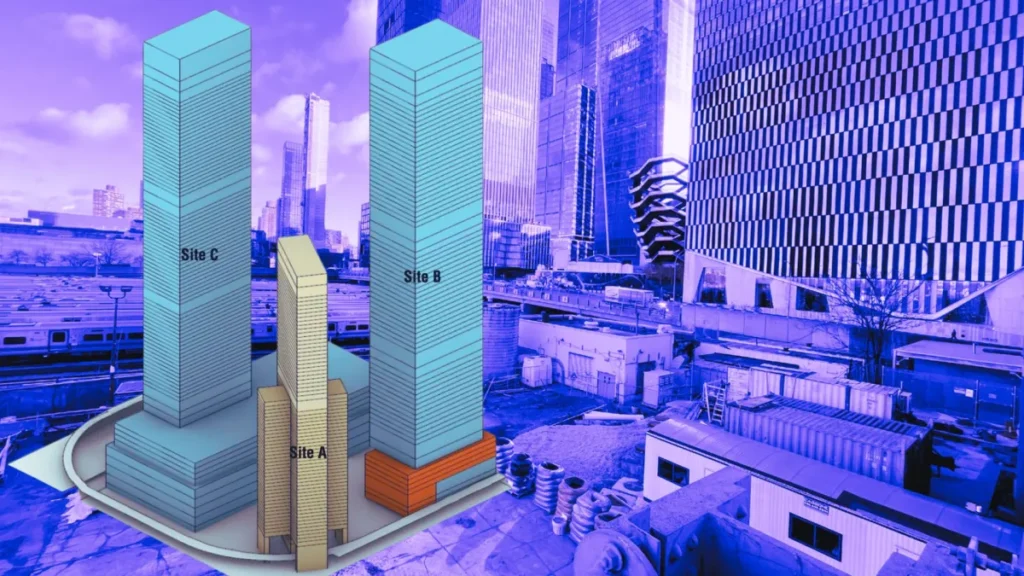

High Line to casinos and skyscrapers, an example of bad rezoning

It opened in 2009 and is now the most famous elevated linear park on the planet. We are talking about the High Line, of course, an urban, public, linear park that has made its mark in New York, in the borough of Manhattan. In just 2.33 kilometres, it is a small jungle of curious vegetation that attracts more than 5 million visitors a year.

Visitors can stroll along its botanical walkway and get to know the various wild plants that grew on the abandoned tracks of the New York region before its restoration. Its greatest peculiarity? It stands on the very rails of a disused railroad track.

But now, this iconic area of Manhattan is threatened by rezoning. More precisely by a neighbouring building project, at the old West Side Yard train station, which proposes to build a casino and several skyscrapers, and to do so right in the shadow of this elevated garden. A prospect that has Joshua David and Robert Hammond, the well-known founders of Friends of the High Line, worried.

In the words of the duo, such a redesign of the site would have negative effects that would spoil the High Line experience. And it would also undermine the effort that went into the community-oriented urban development. I mean, what was, a decade ago, the conversion of this elevated industrial rail line, basically.

But what are the secondary and environmental effects of rezoning?

Goodbye to natural ecosystems. This is undoubtedly one of the worst environmental consequences of redesigning the land. Taking forests and wetlands and converting them into urban or commercial or residential areas is shooting ecology in the forehead. Because by transforming it, you end up destroying the habitat of numerous creatures in the process. Especially since the survival of many of these species is directly dependent on these natural spaces.

In other words, both deforestation and habitat encroachment lead to a drastic reduction in biodiversity. Not to mention that, by changing land use, the ecological functions of these biological corridors are being altered. We are talking about such vital processes as carbon sequestration, soil conservation and the regulation of the water cycle.

Another criticism of rezoning is the increase in pollution. To understand this point, it is sufficient to recall that urbanisation and expansion of industrial areas encourages more factory activity. This in turn leads to higher levels of pollution. Emissions which, of course, affect both air and water quality and the health of neighbouring ecosystems.

A loss of soil sealing, which reduces water absorption capacity on the one hand, and means that waste is washed into rivers and aquifers on the other. Heavy metals and chemicals which, in the end, deteriorate water quality first and threaten biodiversity second.

This is how global warming is increasing, and how vegetation acts as a carbon sink. We have already pointed out: rezoning often brings with it deforestation and the conversion of natural areas into urban or industrial zones. This means that their loss or reduction equates to a decrease in the earth’s capacity to absorb one of the main greenhouse gases – yes, carbon dioxide.

A range of pollution cons and cons, plus the expansion of infrastructure and the construction of buildings. In what way? Because both generate additional carbon emissions. In addition to emissions from building materials, of course, as well as increased traffic and energy consumption in urban areas.

Human health at risk from urban reuse

Parks, gardens and nature reserves are fundamental to people’s well-being, that’s a fact. They are synonymous with recreation, stress reduction and mental health for a reason. The problem? Rezoning often leads to a reduction in the number of these green areas. A loss that, in turn, causes air and water quality to drop, especially in cities.

This, of course, only exposes people to more respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. We are talking about people’s contact with nature being limited, then deteriorating, and finally disconnected from the environment.

In addition to this rain of environmental disadvantages of rezoning, there are other major drawbacks to be taken into account. The overexploitation of natural resources, the vulnerability of cities to natural disasters, the availability and sustainability of water sources. In addition, of course, to the degradation of soils, the drying up of water resources and the exposure of flora and fauna, forced to live and breathe polluting gases everywhere.

Because changing the natural topography for urbanisation is sometimes a recipe for disaster.

Rezoning is a complex and multifaceted process, in conclusion. It is a kind of flexibility of land use that is set in motion from various spheres. From legal and social, to economic and environmental sectors.

Owners and companies, city councils and governments are the first to be involved in this struggle to reuse and redesign and intervene in the land, it is true. But the rest of us are also part of the machinery. And that is why it is so important to understand this term and the risk to which we expose the environment time and time again.

And yes, rezoning is a very useful tool both for economic development and for managing urban sprawl. However, it has significant disadvantages for the ecosystem, and there is no denying that either. Against this backdrop, it is absolutely essential that rezoning plans gradually incorporate action measures. Such as?

Starting with a focus on sustainability and environmental protection, for example. Then by minimising ecological damage, for example. And finally by adopting guidelines that guarantee that future generations will be able to enjoy a real environment. A healthy, ecological and balanced one.