The Arte Povera movement was the most significant and influential avant-garde movement that emerged in Europe during the 1960s (1962 to 1972). He gathered the work of a dozen Italian artists whose most distinctive feature was their use of everyday materials. These could evoke a pre-industrial time, such as earth, rocks, clothing, paper, and rope. The motivation is to provoke thought by working with the materials and observing their specific qualities. These are works that reject the commercial side of art and transform themselves over time as the materials deteriorate. In Arte Povera, the alliance between artwork and nature is indissoluble and the concept of recycling, in a context related to sustainability, becomes crucial. Thus, an artist’s connection with nature is celebrated by using natural materials. Today we will discover together this fascinating artistic period.

How was Arte Povera born and what is it?

In November 1967, the Italian critic Germano Celant published an article in ‘Flash Art’, a recently founded contemporary art magazine, entitled Arte povera. Notes for a guerrilla war. Celant takes note of the development of a system that limits the freedom of the artist, forcing him into weak strategies such as stealing or borrowing from other linguistic systems. He grounds his analysis on the Marxian concept of alienated labor and attributes to the artist the role of eternal warrior. He draws a portrait that can fit almost any artistic strategy developing in the years in which he writes. For example, from Process Art to Performance, to some fronds of Conceptual.

The formula ‘Arte Povera’ simply meant to indicate an ‘attitude’ and not a ‘movement’, a concept that was reiterated in the various expositions. Afterwards, however, it took on the value of defining a true and proper artistic trend. Among other things, it became an excellent promotional vehicle, a sort of ‘brand’ within the commercial network to which the artists themselves declared to be opposed. The artists were mainly supported by the Turin gallery of Gian Enzo Sperone and also by the collaboration of the gallery owners Leo Castelli and Ileana Sonnabend. Skillfully relaunched at the resumption of the art market in the early 1980s, Arte Povera is today considered one of the most significant contributions to the art of the 1970s.

Yet, it is possible to recognize one common element of the Italian group in the radically anti-technological and anti-modernist approach to materials and production processes. This peculiarity is justified, on the one hand, by the Italian delay in the industrialization process. Arte povera is the result of the economic boom of the 1950s and it is opposed to the rhetoric of modernity that characterized the previous decade.

What are the topics of Arte Povera?

In the representatives of Arte Povera, the dualism nature/culture is continuously re-proposed (in Penone and in Kounellis). The use of technologically obsolete and natural materials (paper, wood, fabric) or materials with a long artistic tradition (marble used by Fabro) is essential. The references to classical culture (in Pistoletto and Paolini) and the vitalism with which the recurring theme of energy is colored (from Kounellis to Anselmo). For many the manual ability becomes a central element of the creative process. Moreover, the reference to pre-technological forms of life and civilization (the structure of the igloo by Merz and the Afghan carpets by Boetti). Finally, the constant presence of a poetic and expressive substratum.

Where and who: Michelangelo Pistoletto

The Italian centers that contribute most to the development of Arte Povera are Turin and Rome. Michelangelo Pistoletto (1933) works in Turin. He made his debut in the early sixties with the series of ‘Specchi’, which would recur with a certain continuity throughout his work. At first, these were portraits painted by hand on a reflective metal surface. These will evolve into printed human figures, mostly life-size and on various reflective surfaces. In such a way as to confuse the viewer by integrating him into the artwork, along with the space in which he finds himself. The Mirrors already contain, although deployed in a more traditional and Pop form, the desire to break down any barrier between art and life.

In 1966 Pistoletto presented his first Oggetti in meno, sculptures, and assemblages without unifying stylistic elements, conceived as the externalization of a particular perceptive experience. The Venere degli stracci (1967-1969) belongs to this research. The kitsch copy of the Aphrodite Cnidia transformed into support for an accumulation of rags, in an effective encounter of high and low, classical culture and massification.

Simultaneously, the artist founded a group dedicated to performance (the Zoo Group), with which he realized various interventions. They often take place in public space: this is the case of Globe. A performance in which the artist rolls an enormous ball of newspaper through the streets of Turin, involving passers-by.

Piero Gilardi

Piero Gilardi (1942) shares with Pistoletto the desire to break down the separation between art and life and a strong political connotation. He debuted with Tappeti natura, faithful reproductions of fragments of nature from the shore of a stream to a field of grass. However, it is for his contribution to the exhibition ‘Arte abitabile’ (1966), in which he installed some humble work tools such as a wheelbarrow and a saw, that Gilardi entered the first ranks of Arte Povera and then left it.

Linked to Turin, by birth or by adoration, are also several artists who represent the wing of Arte Povera closest to the sensitivity of American Process Art.

Giovanni Anselmo

Giovanni Anselmo (1934) is interested in the universal flow of energy, as it manifests itself in nature rather than in man-made machines. His works are often active situations of energy, forced into a static form, or intended to change the form of the work overtime. Direzione (1967-1968), for example, is a magnetic needle embedded in a triangular stone, which tends to orient itself toward the North Pole. In Torsione (1968), an iron rod discharges against the wall of the exhibition space the return thrust exerted by a moleskin cloth entangled around the other end of the rod.

In the celebrated Senza Titolo (Scultura che mangia) of 1968, one head of fresh lettuce acts as a buffer between two blocks of granite held together by a rubber band. As the lettuce wilts, the tension between the two blocks is released until, if the lettuce is not replaced, the smaller granite block falls.

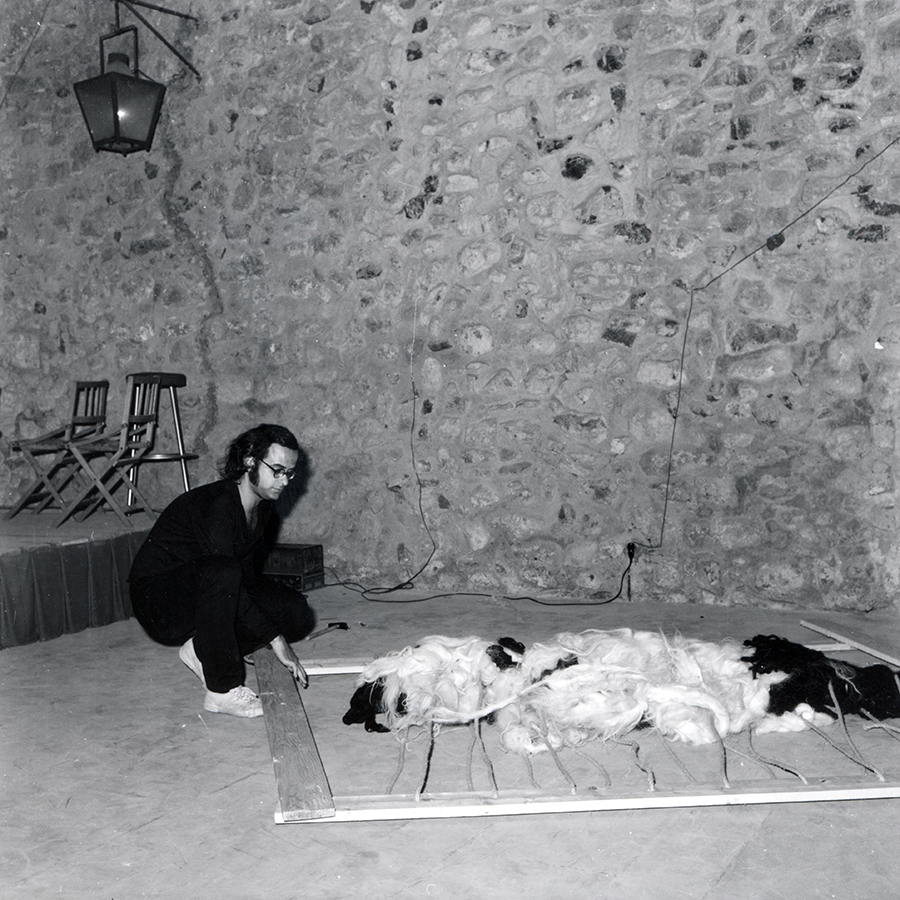

If natural elements often return in Anselmo’s work, it is above all in the work of Giuseppe Penone (1947), also from Piedmont, that they take on a leading role, particularly wood. Penone is particularly interested in the relationship between man and nature and in the reciprocal conditioning that emerges from this relationship.

Giuseppe Penone and his relationship with nature

In December 1968, very young, he performs in the woods near his home a series of actions altogether entitled Alpi marittime. They are all linked to the superimposition of his body and his human story with the forest and its inhabitants. They are a series of photographs taken from 1968 to 1985 in which the artist can be seen relating to streams and trees through small gestures, interfering with their growth without interrupting it.

What exactly does he do?

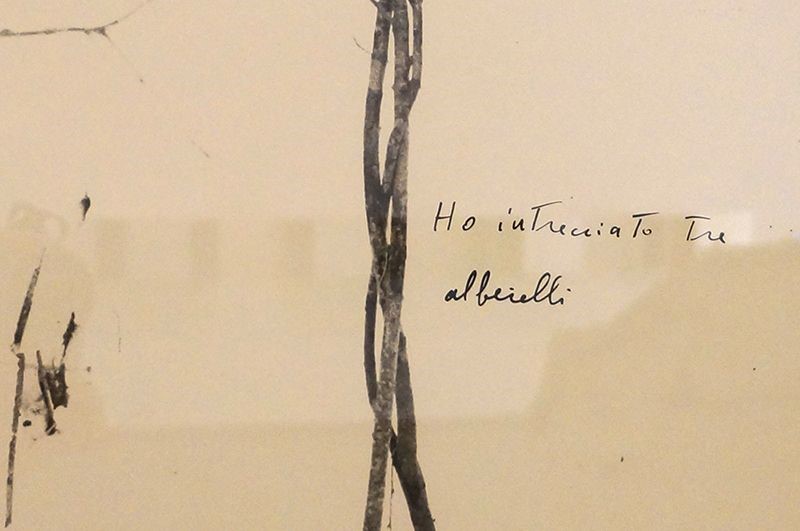

He fixes a metal cast of his own hand to the trunk of a tree, so that, despite its growth, the sign of his contact will be forever visible.In Ho intrecciato tre alberelli (1968-1985) Penone intertwines three twigs to give them an unnatural form. He measures his own height and the length of his arms and constructs with those measurements a rectangle of stones along the course of a stream. In short, his body and his gestures become an integral part of the growth and flow of what he calls the “flow of stones”, the natural growth. The short times of our lives are nothing compared to the very long times of nature. Penone chases it, camouflages himself in nature and germinates together with it.

Other activities deal with the age or size of his body; such as the series Alberi, entitled Il suo essere nel ventiduesimo anno di età in un’ora fantastica (1969). Penone takes a huge abandoned beam and begins to carve it following the growth circles of the original tree until he reaches the one corresponding to his twenty-second year of age.

With this game the artist rediscovers and brings to light nature, hidden by civilization and its rationalizing intervention, but also a vital form that is hidden in the minimal structure of the beam. The game of references also corresponds to the casts, prepared by the sculptor, of centuries-old dead trees within which he buries a new living essence.

Gilberto Zorio, between chemical and natural elements

The theme of energy also returns in the research of Gilberto Zorio (1944), whose artworks often contemplate the activation of chemical or physical processes. More than chemistry, Zorio is actually interested in alchemy as a practice capable of mixing scientific processes and mysticism, research, and symbolism.

Piombi (1968) consists of two lead tanks containing one recycled hydrochloric acid, the other copper sulfate. A copper rod connects one tank to the other, triggering a chemical reaction that produces salts and crystals. Linguistic elements, words, or iconic elements often appear in his works. Like the five-pointed star that alludes to the metaphysical dimension. The javelin, which represents what is mortal, and the canoe, which mediates between the two realms. All always made with poor and perishable materials, susceptible to physical or chemical variations. One of Zorio’s first works (1967) is a tent, an elementary living structure in which saltwater, dripping from above, significantly transforms the work overtime thanks to the evaporation of the water and the corrosive capacity of the salt.

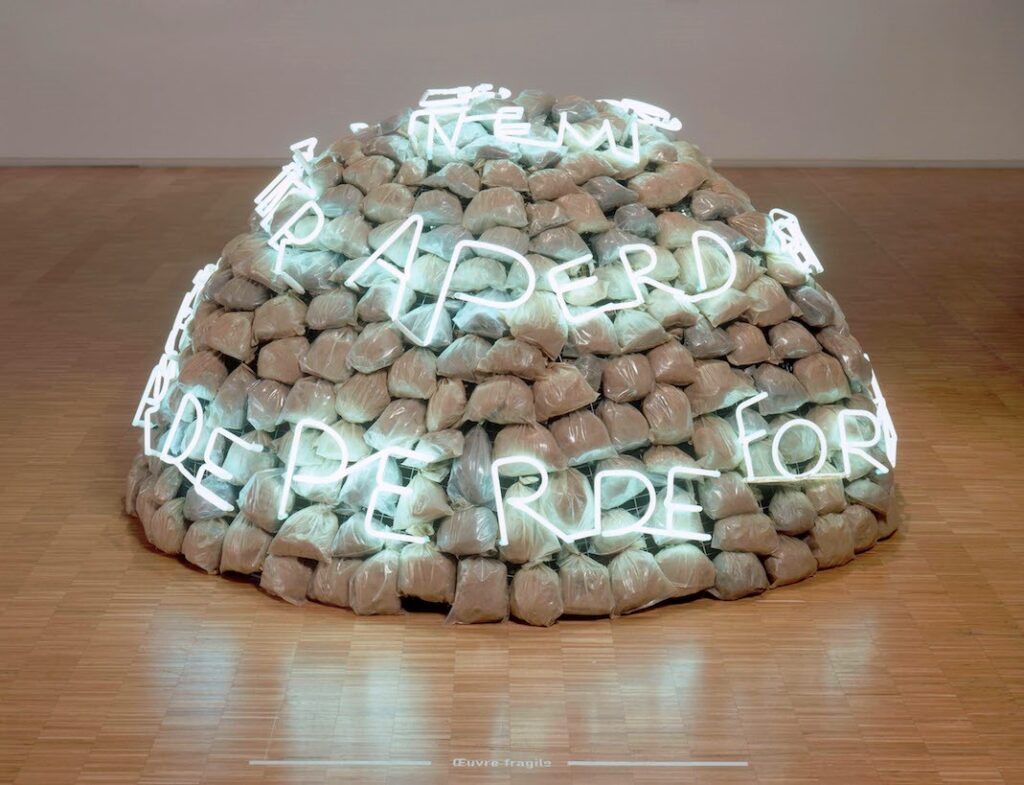

The artistic deepness of Mario Merz

The theme of habitation is particularly dear to Mario Merz (1925-2003), born in Milan but adopted by Turin, who, in 1967, started the Igloo series. His most famous work. After an informal beginning, in the 1960s Merz turned to poor materials and to a language characterized by a few signs and archetypal elements, which, however, always return in different and visually fascinating configurations: the igloo, symbol of the lost purity of pre-industrial society, the spiral, symbol of infinity, and the Fibonacci numerical series, in which each number is the result of the sum of the two previous ones, to evoke the universal laws of growth.

The numbers are usually made with colored neon which Merz often uses to insert phrases into the work that become the title. Object hide, If the enemy concentrates he loses ground if he disperses he loses strength, Do houses revolve around us or do we revolve around houses? or the famous What to do? by Lenin, used for a 1968 work that seems to comment on the current revolts.

Luciano Fabro

On the other hand, in the works of Luciano Fabro (1936-2007) the allusions to classicism become more consistent, extending also to the use of traditional materials, from marble to Murano bronze, and of techniques of craftsmanship in conjunction with poor and modern materials, within a work of extraordinary ethical and conceptual rigor. All this is particularly manifest in the Italie series, which Fabro began in the late sixties and which was to accompany him throughout his career. Indeed, the subject is susceptible to an infinite series of variations of recycled materials and configurations. It may be a street map covered with lead sheets and lying on the ground, or a silhouette cast in gold upside down in front of a mirror.

With Fabro, we enter the colder and more conceptual line of Arte Povera, to which Alighiero Boetti, Giulio Paolini, and Emilio Prini also belong.

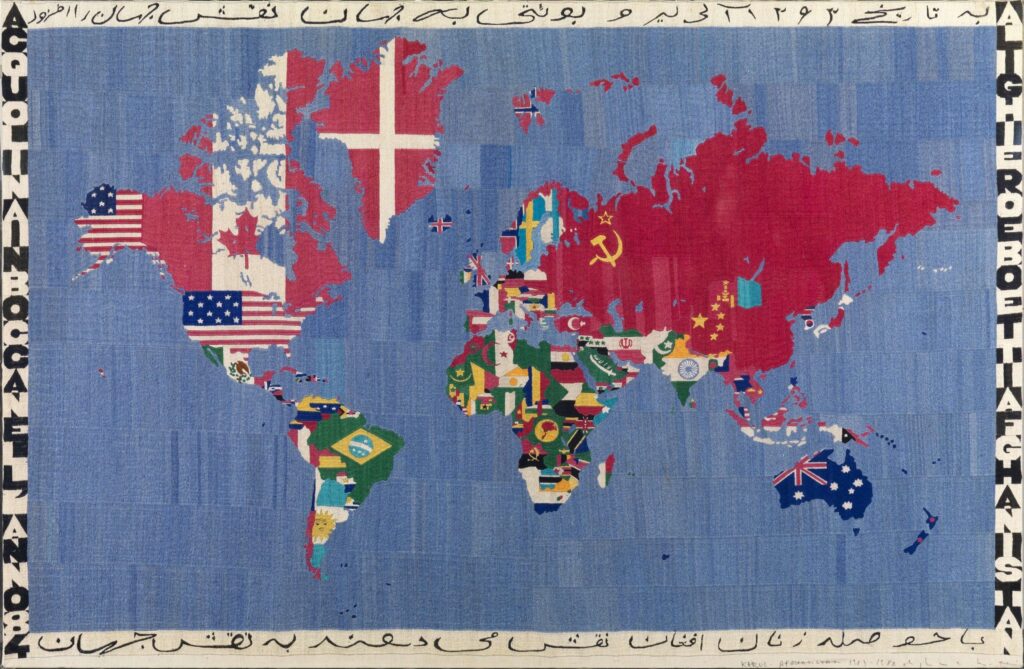

Alighiero Boetti: word games and meanings

Alighiero Boetti (1940-1994) is one of the most important personalities of Arte Povera and, in general, of the 1970s. In fact, Boetti participated in almost all the collective exhibitions of this group. But he always carried on his personal research and experimentation, without identifying and locking himself in a single movement. It is probably the concept of duplicity that is the key to interpreting and understanding the vision of this artist who, in 1973, decided to change his name to Alighiero and Boetti; almost as if two opposing but inseparable identities lived within him.

Far from the classical schemes of painting, which Boetti considered too distant from common life, his works are characterized by continuous changes and research. Both in the themes and in the techniques and materials used.

The volcanic ideas of Alighiero Boetti

Endowed with a complex and varied culture that ranges from philosophy to mathematics to alchemy, Boetti made his debut in 1966 with Zig-Zag. A frame on which is mounted a cheap fabric, found as waste, decorated with abstract motifs, in which he plays with the abstract tradition of Modernism. In the same year, he created Lampada annuale. A minimalist black box containing a light bulb that lights up for a few seconds once a year, according to a totally random rhythm.

In the following years, Boetti shows a growing interest in the systems of classification in nature. The quantification of what is apparently not measurable: an interest that is repeatedly found in the conceptual field, and that in 1970 produced the artist’s book Classifying the thousand longest rivers in the world. The same interest explains the series of Mappe. Planispheres translated into ecological tapestries in which the political borders of each country have the colors of their respective flags, created from 1971.

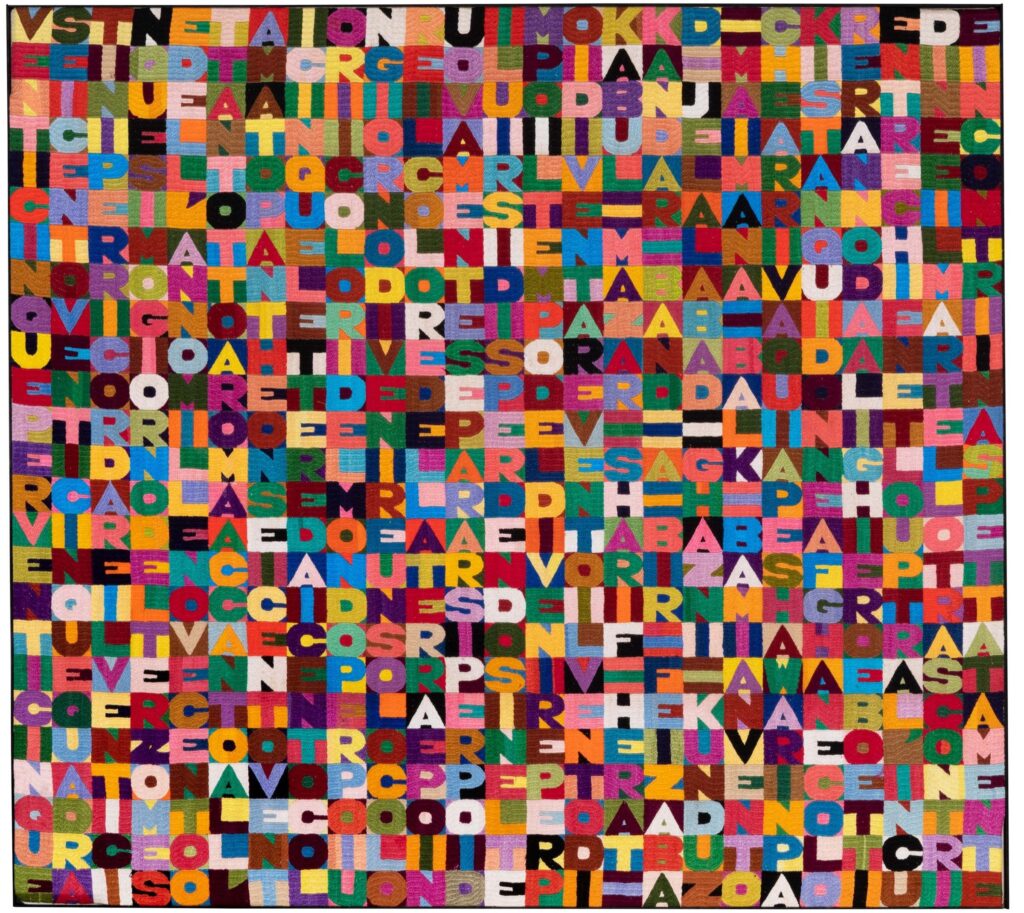

For the maps, as well as for the alphabetical tapestries created in the same years – in which short phrases or more complex texts, arranged like a chessboard according to different patterns, alternate with non-Western codes or alphabetical systems, mathematical and combinatorial schemes – Boetti relies on Afghan manufactures, a country he is very fascinated by and where he spends part of his life.

The experience in Afghanistan and the colorful tapestries

During a trip to Afghanistan in 1971, he was fascinated by the ancient art of linen thread embroidery practiced by local women. So he decided to commission the work to 500 women who would perform it strictly by hand. Thus were born the famous tapestries that have made him famous throughout the world.

In different formats, the tapestries were divided into grids in which sentences and mottos invented by the artist himself were inserted. Through apparently simple but discordant words, the artist pondered on political, social, cultural, and linguistic aspects. He invites the spectator to question himself and actively enjoy the works, without suffering them in a passive and disinterested way. In a continuous game of double mirror made of right and left, high and low, words and images, he reflected on the duplicity of human nature and society, between coherence and contradiction.

The ‘thread’ of thought

The collaboration with the Afghan weavers lasted many years, even when they were forced to flee to Pakistan following the siege of the Russian troops. Boetti continued to provide his precise indications and the production did not stop, despite evident technical changes, due to the use of sewing machines. However, the main objective did not change. The viewer is “captured” by the bright colors and the apparent three-dimensionality of the works, but then the paintings need to be read, observed. He is therefore invited to turn, to move around, to think, to question himself, and to elaborate his own personal interpretation.

Therefore, by outsourcing the work, the artist delegates to his collaborators most of the aesthetic and chromatic choices, limiting himself to providing the project. The same happens with the numerous pen-and-ink or felt-tip pen works made during the 1970s and 1980s; on subjects such as maps and airplanes, which fascinated Boetti for the contrast between apparent disorder and profound order.

The Contribution of Giulio Paolini to Arte Povera

The work of Giulio Paolini (1940) initially focuses on the basic aspects of the language of painting and art. In particular, the artist has repeatedly indicated the basic structure of his entire work in his 1960 Disegno geometrico. A rough canvas on which he traces, in pencil, the fundamental outline of each figurative composition.

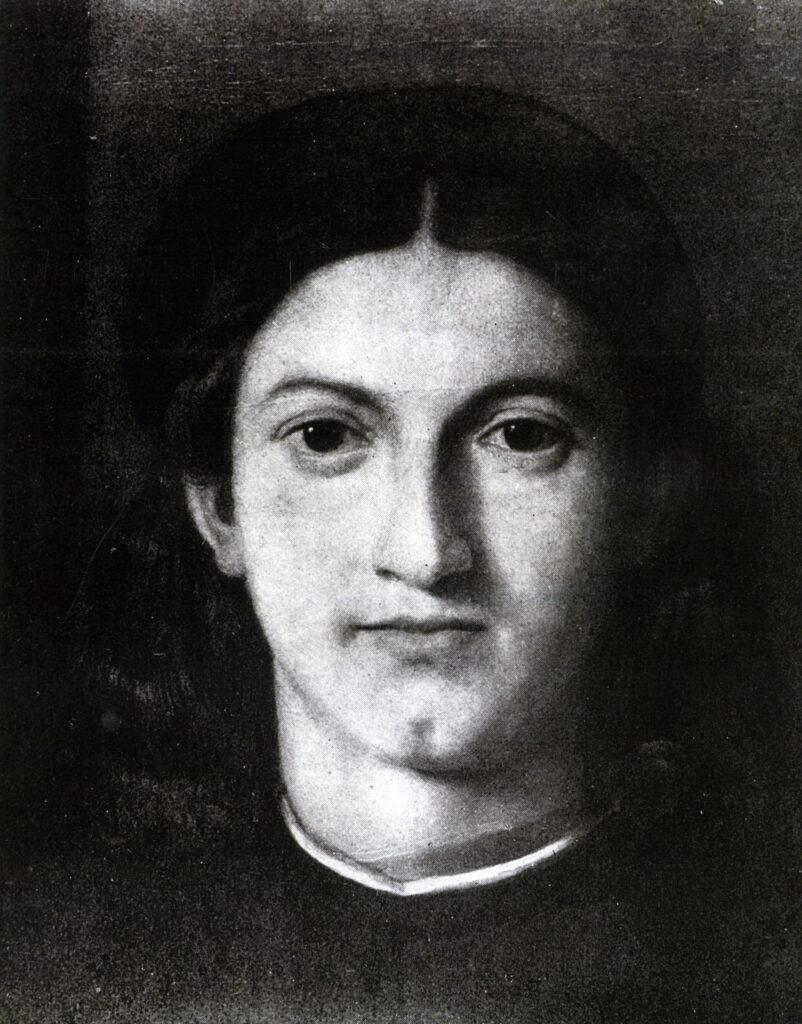

Paolini investigates art and the logic of its museum presentation as a codified system of which he is responsible for bringing to light, revealing, or contradicting the rules. The Giovane che guarda Lorenzo Lotto (1967), for example, is nothing more than the photographic reproduction of a portrait of Lotto, in which the title is sufficient to shift the attention from the concept of portrait to the logic of the gaze. A theme that will return in the numerous installations that have as their subject plaster casts of classical statues; often duplicated in such a way as to become spectators of themselves.

Arte povera teaches us that with humble, natural, discarded and rejected elements we can confess and promote the human condition.

As we have seen, the art world is no stranger to the increasingly discussed concept of environmental sustainability. On the contrary, it is the precursor of living and creating in compliance and with respect for environmental values. In the 1970s, after Arte Povera, Land Art was born in America. It placed nature at the center of the artistic discussion, using natural materials to compose the works, making them perishable. If you want to know more I suggest you read ‘Spiral Jetty by Robert Smithson’.(https://www.thegreensideofpink.com/2020/11/11/spiral-jetty-di-robert-smithson/ )and ‘Richard Long and the dialogue with nature’ (https://www.thegreensideofpink.com/2020/12/02/richard-long-e-il-dialogo-con-la-natura/ ).