They represent an ancient textile tradition and today they are more trendy than ever: contemporary tapestries personalize any room and are increasingly sustainable.

In previous articles, we dove into Land Art and then discovered Arte Povera. We also did a little dive into Street Art, moving from Utha’s America to the Pampeago Alps. Today, I will take you on a long and fascinating journey. We’ll talk about textile art, fabrics, and embroidery. And how they give life to tapestries.

Tapestries: the soft art

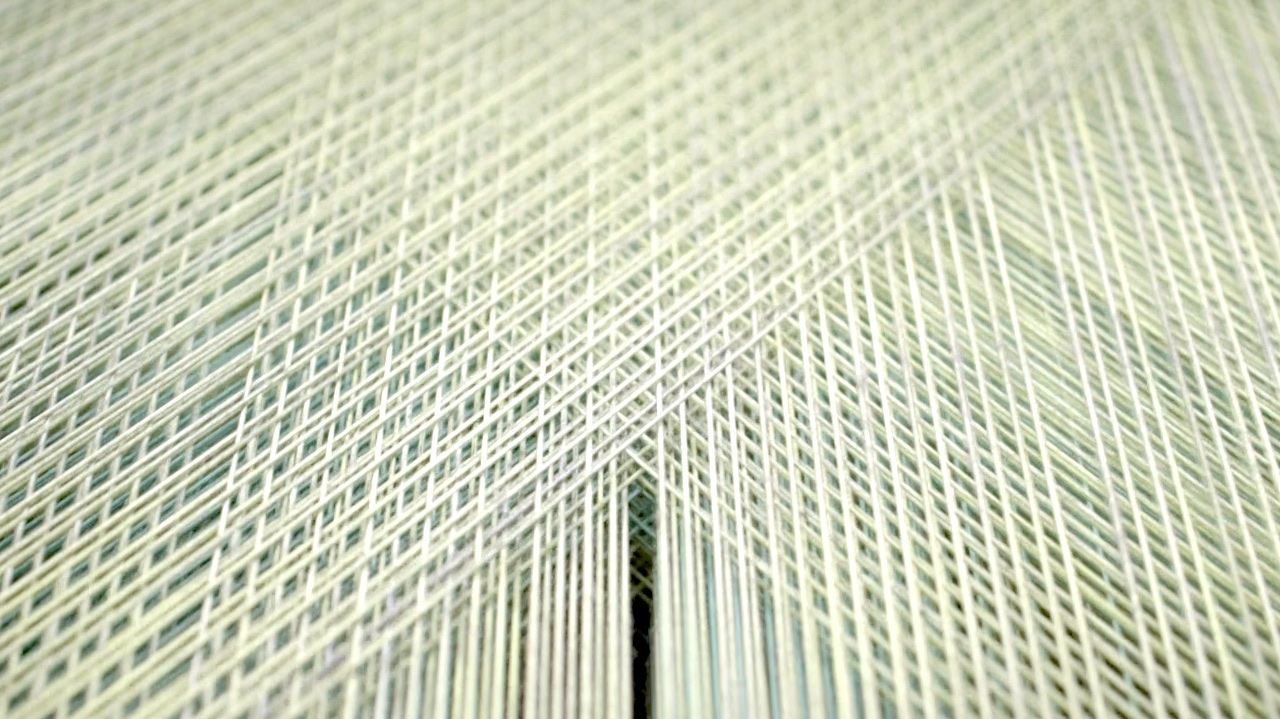

Halfway between craftsmanship and art, tapestries represent an ancient and undoubtedly fascinating form of textile art. Technically it is a weft-dominant fabric, handmade on a loom and intended to cover walls. Usually, of large format, it represents large and detailed drawings. Today the term is improperly used to indicate various artifacts that hang on the walls made with different techniques, such as the half-stitch, the Jacquard loom, embroidery.

Their success began in the Middle Ages when in the French town of Arras these large fabrics were produced from the drawing of a painter, preferably a famous one.

But the origins of the tapestry are probably even more ancient. They even date back to Ancient Egypt and Greece, not to mention the fact that its spread was capillary. There are fine examples in Japan and even in pre-Columbian America.

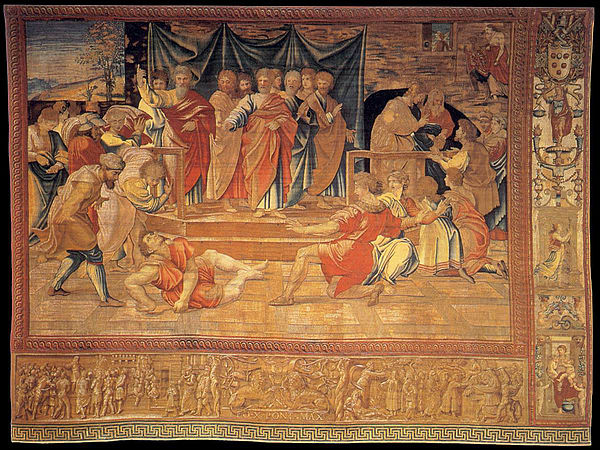

The most important artists of the modern and contemporary ages have tried their hand at this practice, creating preparatory cartoons for beautiful tapestries: from Raphael to Picasso, from Mirò to Boetti. Today tapestries still represent a fascinating universe for many artists and designers, who experiment with innovative fabrics and materials, combining beauty, style, and, above all, sustainability.

Historical background: use and production

Hung on the stone walls of castles, in large rooms that were difficult to heat, they combined a decorative function with that of thermal insulation during the winter. The great success of tapestries over the centuries is probably linked to their portability. Kings and nobles could roll them up and take them with them when moving from one residence to another, and unlike frescoes, they could be saved in case of fire or looting. In churches, they could be unrolled on special occasions.

Sustainable from the start…

They have been produced since the most remote times, even if the difficulty of preserving the materials they are made of – natural textile fibers such as wool, cotton, or flax – has strongly affected the quantity and quality of the finds.

The oldest tapestries that have come down to us date back to ancient Egypt and late Hellenic Greece, but they were common everywhere in the world, from Japan to pre-Columbian America.

Coptic tapestries, which came from Egypt in the first centuries of the Christian era, already showed great technical skill combined with very complex designs.

Manufactures

In Europe, the development of tapestry dates back to the beginning of the 14th century, first in Germany and Switzerland, then in France and Holland. The peak of production was reached during the Renaissance, particularly in Flanders and France. The royal Gobelins manufactory, founded in Paris in 1662, continues producing today.

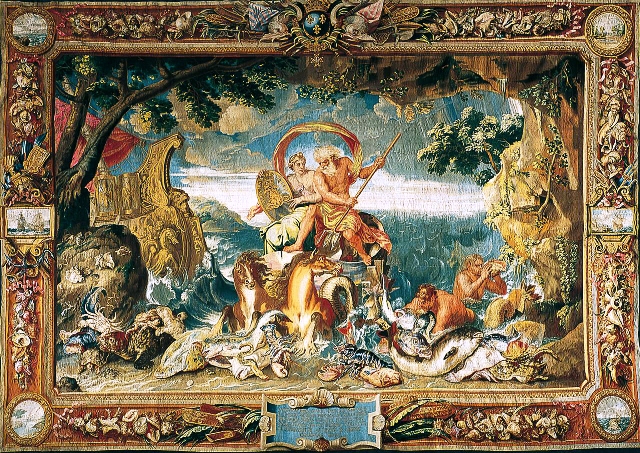

In 1675 there were more than 800 exceptional artists and craftsmen in the circle of the Gobelins, the historic French tapestry weaving workshop. At the orders of the painter Charles Le Brun, there were lapidaries and carpenters, engravers, goldsmiths, upholsterers, and painters of all backgrounds.

The perfection of color and design reaches its apogee in those years. A refinement never reached before in the weaving of tapestries.

Production times can exceed 5 years, due to the complexity of weaving techniques, and consequently, prices increase significantly.

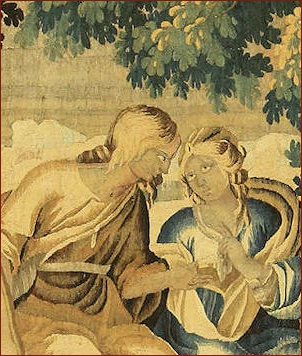

Around the 17th century, the first tapestries painted on silk and flax appeared in France and Italy. These painted tapestries were used for the decoration of royal residences and palaces, so much so that they officially appeared in the collections of the crown. In the “Register of the Superintendent of the Crown” of August 11, 1689, four moaire tapestries painted by the master Bonnemer in the Gobelins manufactory were recorded, illustrating “The Passage of the Rhine by the Prince of Condé’’.

An ordinary painter for the King of France and a collaborator of Charles Le Brun, Bonnemer had learned the technique of painting tapestries on silk, tapisseries de peinture, during his stay in Rome.

In 1715, upon the death of King Louis XIV, the inventory of the crown’s furnishings listed a remarkable 2,155 Gobelins tapestries.

The painted tapestry – Gobelins tapestries

The technique related to this production of painted tapestries, mentioned several times in the “Register of the Superintendent of the Crown”, seems shrouded in mystery, the information is rare and jealously guarded.

In the Gobelins manufactory itself, one tapestry maker does not reveal to the other the secret of the tapestry’s fabric painting technique.

These are the origins of the production process of Editions d’Art de Rambouillet tapestries. The French company de Rambouillet, drawing on techniques used in the XVII century, devised in 1960 an exclusive process of reproduction of antique tapestries painted on fabric.

It took seven years of research to achieve the desired result that we can now appreciate in the Editions d’Art de Rambouillet tapestries.

The decline of a great art

From the end of the 18th century, with the transition to industrial production and the increase in the cost of labor (very long processing times determine prohibitive costs), the fashion of tapestries began to decline as an outward manifestation of the prestige of the aristocracy and was affected by the strong social changes of the moment. During the French Revolution, the crowds burned them not only to recover the gold filaments woven into the tapestries but also to destroy the banners of the defeated class.

Following the crisis, which involved all of Europe, Italian tapestries closed their doors. The art of tapestry survives today in small areas of production and restoration of antiques.

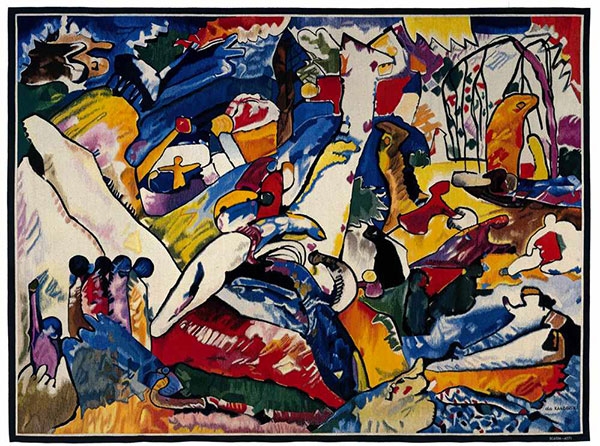

In the ’60s, on the impulse of the artist and cartonnier Enrico Accatino, an innovator and promoter of textile art in Italy, the revival of this technique. Inspirers of these workshops are the works of contemporary masters such as Afro, Capogrossi, Accatino, Casorati, Guttuso, Klee, Kandinskij, De Chirico and Cagli.

Materials

For the preparation of the warp, flax and wool were used. Today we use twisted cotton, more elastic than flax and less unstable than wool. For the weft is mainly used wool and silk, very used in the past. The latter is less frequently used, in some cases alternated to wool in order to obtain particular contrasting effects. Wool yarn must be combed and it is coupled, doubled, or tripled and more, in order to reach the size needed for the weft. This coupling allows, by joining yarns of different colors, to obtain every slightest shade of color (if the colors are similar) or picché effects (if the colors are contrasting).

Contemporary tapestries: the signature of sustainability

Creatives

Just as in the past, young creatives today love to confront themselves with textile art. Among the emerging designers who continuously confront themselves with this practice, there is Vanessa Barragao, a Portuguese designer who uses waste materials from textile factories for her tapestries. With truly surprising results: her tapestries in fact evoke seascapes, made of colorful coral reefs and fantastic creatures.

Designing and making rugs in a totally personal (and sustainable) way is the mission of Portuguese designer Vanessa Barragão. Since 2014, reusing yarns wasted by industry, she uses ecological weaving techniques to create collections that reproduce the beauty of marine ecosystems. Modern rugs and tapestries that, in addition to being beautiful, emphasize the need, for those who make design, to make a difference even with very simple gestures such as the reuse of materials and the use of craftsmanship such as crochet or embroidery.

Hence the watchword of her work: upcycle, or creative recycling, carried out, in each carpet and tapestry, with the waste materials (and their colors) found from time to time. The result is always different, but the protagonists remain the same. The atolls, corals, seaweeds, and mushrooms that for Vanessa represent the inhabitants of the most beautiful and complex microcosm that exists on Earth.

Soundproofing

Who said tapestries are only decorative? Casalis has created Ondo, a series of noise-absorbing panels made with a three-dimensional wool structure. Thanks to their particular combination of waves – made of Trevira polyester and designed by Aleksandra Gaca – these tapestries perform not only an aesthetic function but also a practical one (especially in places in the house where you want to muffle sounds). An object that combines functionality and beauty, as well as sustainability, since they are made of environmentally friendly materials.

Sustainable

Natural materials such as Himalayan wool, silk, or hemp and a long manufacturing process by Tibetan craftsmen in Nepal. These are the ingredients for the creation of unique and original collections by Cc-tapis. The brand does not aim at mass production but gives the customer the possibility to create the desired carpet and the ideal size, without using chemicals, acids, or artificial fibers. From rugs to tapestries, Cc-tapis offers colorful and creative solutions, thanks to numerous collaborations with emerging and established designers.

Scandinavian

In pure white, or in natural colors and inspired by nature: these are the Scandinavian tapestries, now very trendy. Strictly handmade, preferably in wool (or cotton), with bangs or embroidered applications, the effect is assured.

Recycled plastic tapestries

In 2019, the ‘A collection’ project kicks off in Turin: an exhibition of 10 large tapestries made with yarns derived from processing and recycling plastic fished from the sea.

The project is the materialization of a simple assumption: the yarns obtained from recycled plastic, thanks to their infinite colors and materiality, can compose detailed and refined tapestries. Plastic, mostly coming from small bottles that pollute the seas, is processed through a mechanical process of melting and spinning. The transformation of the so-called second raw material is carried out in an ecological, sustainable, and productive way and proceeds to the final stage in which delicate handling systems make it possible to obtain yarns that perfectly simulate those of natural origin. Indeed, their characteristics are further enhanced.

According to an ancient Persian proverb, “A Persian carpet is perfectly imperfect and precisely imprecise”. Why? It’s really simple. A fine Persian carpet always has imperfections to show how only God can create perfection.