He was born in Burkina Faso, studied in Berlin, and returned to his country to build his city’s school. He is now one of the leading representatives of sustainable architecture.

“Only those who are involved in the development of the process can appreciate the results achieved, develop them further, and protect them.”

With these words, Diébédo Francis Kéré sums up his architectural philosophy, in which he involves communities and uses local materials.

A philosophy that can be seen from the very beginning of his career.

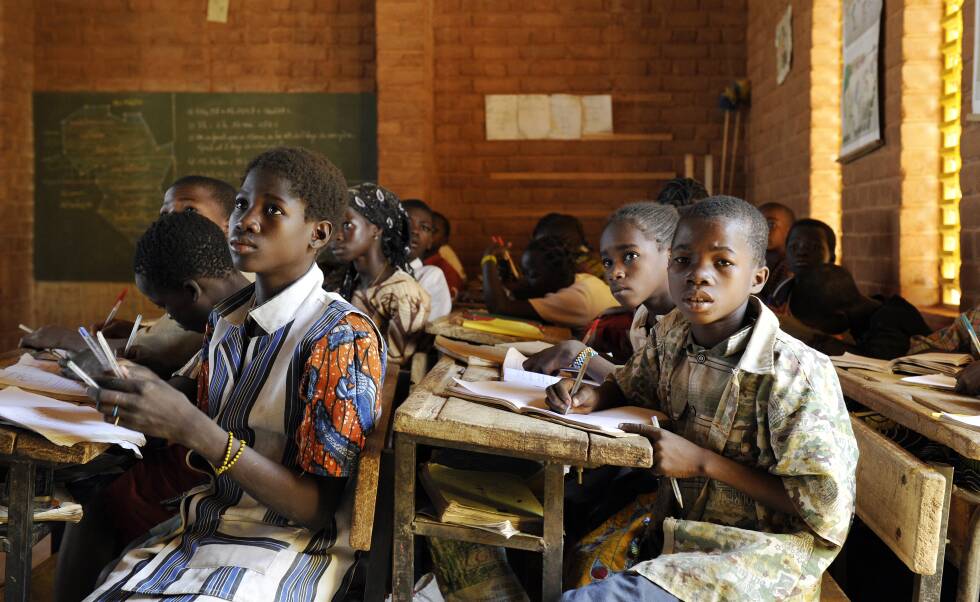

Indeed, in 2001, fresh from graduating from Berlin’s Technical University, he began building the first elementary school in his home village of Gando, Burkina Faso.

Through a combination of contemporary techniques, education and public engagement, he has succeeded in creating innovative buildings. So extraordinary that he attracted international attention and immediately won major awards such as the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2004.

First sustainable project: the Gando school

As Kéré himself explains in introducing the project, the aim is to create an environmentally sustainable building, constructed from materials already found in Burkina Faso, especially clay.

By bringing together affordable and abundant materials with a contemporary engineering technique, Kéré creates structures made to last.

Buildings that can protect against the region’s hot climate through natural ventilation that eliminates the need for air conditioning.

In addition, the fusion of innovation and local techniques makes it easier for people to maintain (in the long term).

Eliminating the need to import other materials reduces the environmental impact in both transportation and construction. In addition, local workers are used and trained, also avoiding the cost and impact of bringing in consultants and technicians from abroad.

The key part of the project is precisely due to the training of local people. Indeed, this social architecture puts education as the central part of sustainability. It also reminds us of the importance of being able to conserve buildings, without expecting economic support and aid from abroad.

To be sure to actively engage the population (the majority of whom were illiterate) Kéré explains the projects to them by drawing them in the sand and listening to their suggestions.

“I consider my work a personal assignment, a duty to this community. We have to fight to create the quality needed to improve people’s lives.”

Adam Hencz, in his article published by Artland Magazine, reminds us of how each eco-project of Kéré Architecture (the firm he founded) is above all a social commitment.

Politics and sustainability: The National Assembly

The proposal by Kéré Architecture for the construction of a new building had sparked in 2014 after the previous building was razed by insurrections. These insurrections had ended the government of President Blaise Compaoré, and the architectural design was intended to reflect this turning point in Burkina Faso’s history.

Andres Lepik, in his article published by Domus, explains how the goal of this immense pyramidal construction would be to allow citizens to gather in front of the Parliament and access it through a complex of stairways and terraces with gardens. Just as in the Reichstag in Berlin (renovated by Norman Foster in 1999), the signal emanating from this building is the idea of democracy.

Unfortunately, due to the political situation in the country, the project has not yet been realized.

Symbolism for the National Assembly in Benin.

One government project still under construction is the one in Porto Novo, Benin.

As James Parkes, writes in his article in Dezeen, the building will mimic the structure of palaver trees, traditionally used by West African communities as universally accessible places for assemblies.

Begun in 2019, the National Assembly will cover 35,000 square meters. Like all buildings conceived by Kéré, it has an integrated ventilation system and careful consideration of surrounding site conditions.

The offices will be located in a crown sheltered by a façade that will act as a filter for sunlight, preventing them from being overheated but receiving sufficient natural light.

Part of the site will be left for a natural park where local flora will be allowed to grow, providing the city of Porto Novo with a recreational space.

The park itself will reach all the way down to the roots of the palaver tree, providing a large space for public assemblies that will reflect those taking place inside the building.

Kéré Architecture has used the same expertise that nimbly balances sustainability with technical skill in other African countries such as Kenya, Uganda, and Senegal.

Respect for trees: Goethe Institut Dakar, Senegal

Under construction since 2018, the Goethe-Institut is housed between a residential area and a lush garden. The project aims to be both respectful of the surrounding environment and contain enough space for the many activities offered.

To accomplish this, it created a two-story building, formed to reflect the shape of the trees that have always been present at the site.

The structure functions as a shield to simultaneously protect neighbors from noise from the institution and building occupants from noise pollution from outside traffic. Once again, mainly local materials were used, and the entire project is designed to have a very low ecological footprint.

Another important feature of this project is also on the ideological level: the one in Dakar is the first Goethe-Institut building to be purpose-built and by an African architect.

An attempt to rid themselves of the consequences of their previous political colonization and contemporary economic colonization has been underway for years in many African states. This project is an illuminating example of the future of African architecture. Indeed, the model shown by Kéré shows how it is possible to conceive of a new postcolonial architecture based on the relationship and dialogue between two cultures.

The Pritzker Prize

The award in 2022 of the Pritzker Prize to Francis Kéré marked a turning point. For the first time, it was an architect born in Africa and committed to social and sustainability for decades.

With his skill, Kéré provides evidence of the extraordinary evolution of the African architectural scene in search of a new post-colonial identity.

In awarding him, the Pritzker jury declares, “He shows us how architecture can reflect and serve needs, including aesthetic needs, of populations around the world.”