Can landscape be considered an architectural material? It is not easy to answer this question. What exactly is the “material” we are talking about? It is only a material element. Or is it not?

The word landscape has several meanings. One is that referring to perception. We are placed in a context of which, through vision and culture, we learn to read meanings. Meanings that come to us from the gaze. The perceptive one but also the ‘mental’ one. The latter is a primary tool for understanding the landscape. It shows us the characteristics that distinguish it. Learning to distinguish it from considering it a mere representation. In fact, by the term ‘landscape’ we also mean the set of the typical elements of a given territory. Including human settlements. In this sense, perhaps, we can identify landscape with a (real yet abstract) material of architecture.

Reducing the negative impact

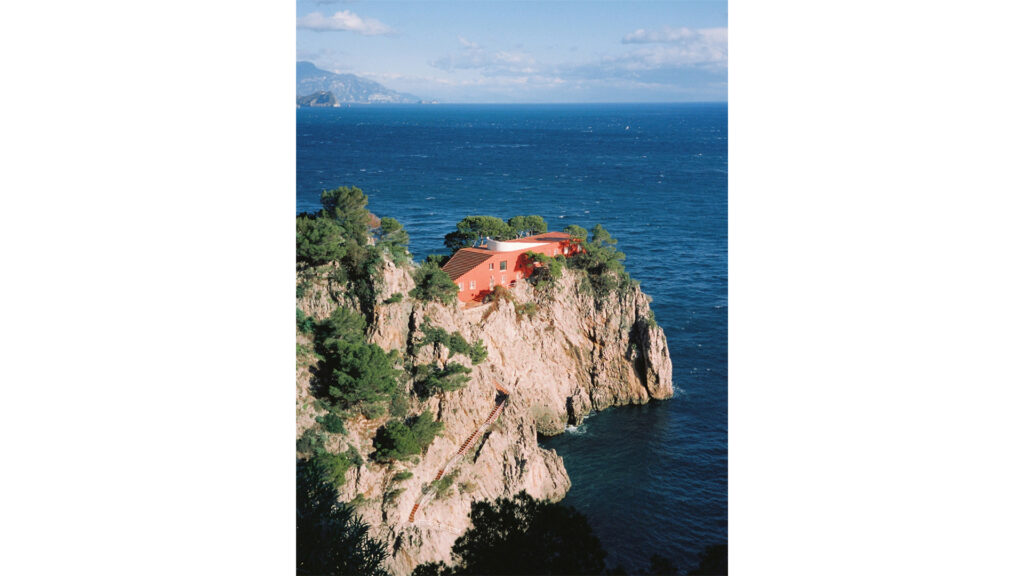

There is, however, one thing that cannot be doubted. Environmentally friendly buildings often have a very good use ratio in terms of energy resources. In other words, those architectural concepts in which the focus is on ‘reducing the negative impact of the building’ place architecture on a higher level. Almost to the point of leaving no disfiguring traces on the landscape. Incorporating the environment into the project. Indeed, becoming the project of the environment. A whole between building and nature. The famous Villa Malaparte on Capri is a precious example of this. But perhaps there is a further step that we can describe. In the perspective of safeguarding the “material” landscape.

Preserving the habitat

In a world where minimising disturbance to the environment has never been more important, architecture has a responsibility to align with nature. Rather than disturbing or, even worse, altering, deforming or reconfiguring the habitat, which instead demands to be preserved. It is about respect for the environment. Making sustainable choices. And, therefore, reversible. That do not harm future generations of human beings, animals, plants. In general, to all inhabitants of the planet. With this in mind, one can reflect on what it means to assimilate with the world as it is. And as it has been since time immemorial. Merging with the place where we are. Becoming part of it. A continuation of the landscape.

Integrating architecture and environment

The starting point is to use natural materials. As natural as possible. But what happens when the setting, the landscape on which we build, is used as an essential part of a building?

A building rests on top of a small hill. In a dense forest. Where a building wraps itself around the treetops. Using the morphology of the land to create areas on several levels. Where environments can be built. Wrapping around a forest. Where the curvatures of the building are built according to how the greenery has grown and will continue to grow.

Rock dwellings are a typical settlement site. From prehistoric shelters to megalithic settlements. Ever since humans realised their extreme vulnerability, they have sought out natural rock formations for protection. In canyons, in rock settlements. In inaccessible places. Perhaps embedded in a rock face, to allow observation and garrisoning of a portion of territory. Hidden from view, on rough walls that evoke the equally rough texture of cliffs.

Taking into account their position under the sky. In hypnotic starry nights to be observed, discreetly. Not to disturb the view and minimising the potential for light pollution.

A core of contemplation. Aimed at increasing awareness through the landscape. Where the landscape becomes a building. Resulting in something that is enclosed but, at the same time, is connected with wild nature.

Natural materials

One aspect to focus on is natural materials, which represent the generative elements of the landscape. Stone, natural textiles, wood and glass. In contact with the surrounding landscape. Which becomes the fifth element; the fifth material.

If it is essential for architecture to integrate and adapt to the natural world, the opportunity to adapt design to what already exists is the fundamental starting point. Construction and demolition are high impact factors. And reducing the amount of times we build and then demolish is essential.

Nature also flows through architecture. In parks (urban and suburban). Without constituting a tear-down but instead enhancing what can be gained from the landscape.

These, in a nutshell, are the points of reflection regarding the interpretation of landscape as a real material of architecture.

Read more: What is Bioarchitecture.

You may also be interested in: Travelling without doing harm.