According to some observers, in recent decades there has been a progressive disconnection between what architects design and what people want. Or what they really need. The future of shiny (and impressive) buildings dominating urban skylines is beginning to look anachronistic. An “out-of-this-world” future. One that leaves a general feeling of a world moving in the opposite direction of what is desirable. But if the probable future of the city is not at all desirable, what can really be done about it? After all, the probable future of cities may not necessarily be limited by what is realistic.

Reasonableness

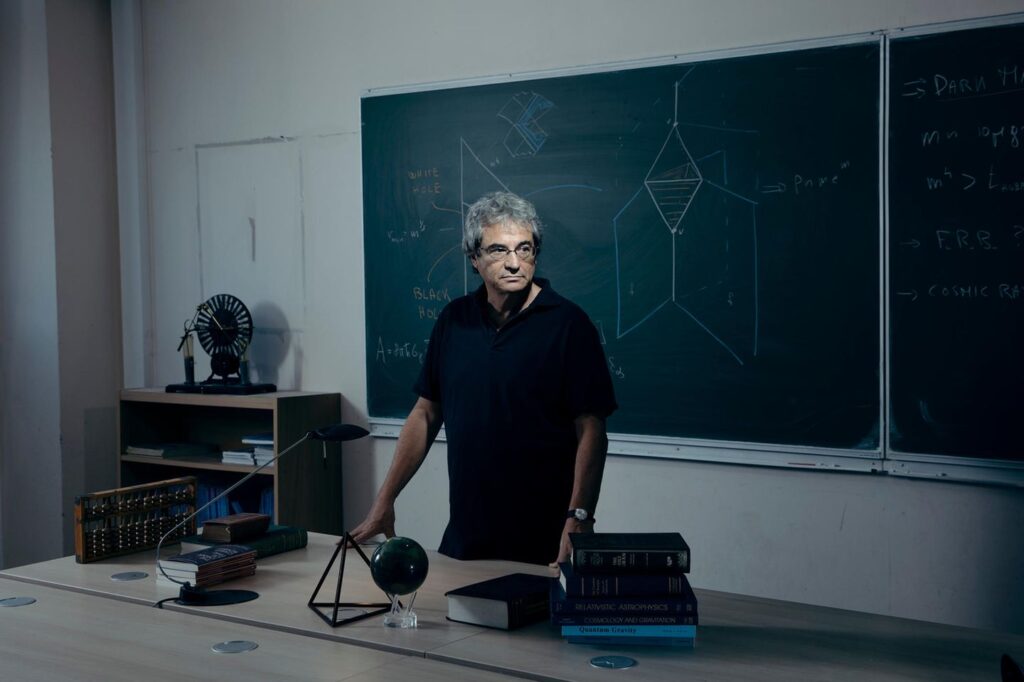

When asked about the probable future that awaits us, physicist Carlo Rovelli stated: “I would say that science does not save us. It saves us our being human, our reasonableness. What saves us, if we are saved, are the things that we think are right and that we manage to do together“. We are all under the same roof (or under the same sky) one might say. Awareness of this should be able to provide the goals to aim for. For the common benefit. “If we continue to think that the goal is to be stronger than others, we are all weaker in the end”, Rovelli concludes.

What architecture can be

Projects that do not attract attention with flashy designs or imposing glass façades. But which focus on sustainability, preservation of local culture and real impact on the community. Pushing the boundaries of creativity and functionality. Redefining what architecture can be. Reinventing traditional techniques and experimenting with unconventional materials. Challenging, in a word, the status quo. By asking the simple question (always a difficult one to answer) of how to do it better. By embracing context, connecting design with history and giving local materials and techniques the utmost importance.

Innovating with tradition

Today, technology has overshadowed tradition. A different approach would be a fusion of past and present. History is not just something to remember. It is instead a basis on which to build the future. Such is the case with the Timber Bridge on the waterfront in Gulou, China. Designed by LUO Studio and built entirely of natural pine wood. The bridge uses ancient Chinese arch techniques. It was assembled on site using a combination of traditional joinery and modern steel-reinforced elements. A method that combines historical practices with modern technology. It also provides flexibility to the project in integrating with its context. A key element of the bridge is its covered corridor. A memory of traditional bridges revisited to enhance the user experience.

Beyond conventional materials

Learning from the past can be a key. But innovating can also mean creating works using unconventional materials. Even to proclaim the centrality of sustainability and creativity in architecture. As US researchers working with SHoP Architects have done. They have created an alternative to steel and concrete as a structural material for floors. These are recyclable panels made entirely of bioplastic derived from a combination of PLA (a bioplastic derived from corn residues) mixed with wood flour. This flour is produced from wood processing waste.

The prefabricated panel was created using 3D printing by researchers at the US Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL). And the University of Maine (UMaine). Both are part of the SM2ART public-private partnership. According to the team, the SM2ART Nfloor panel is better for the environment and faster to produce than similar steel and concrete elements. Elements that are typically used in multi-storey buildings.

Building with a purpose

At the heart of this work is a holistic approach. An approach that refuses to separate design from its intended purpose. Whether it is reviving ancient techniques or rethinking the use of materials. This shows that architecture can also be meaningful in understanding and interacting with context. Be it social, cultural or environmental. In these cases, the project is as much a process as the outcome of a finished product. And these two phases always involve the communities in which it intervenes. Thus promoting a sense of shared ownership of places.

The future, as we see it unfolding, may not be that “desirable” future we have mentioned. To make it so will require a convincing model for architecture. While design has long been grappling with the challenges of sustainability, preservation of cultural heritage and social responsibility, working towards a desirable future requires a method. Capable of generating ideas that are not only innovative. But also deeply welded to the communities they are meant to serve. Architecture that learns to listen and build with purpose.

Read more: What will the architecture of the future look like?

You might also be interested in: Textiles: a tool to reduce environmental impact.