Surely, on more than one occasion, you’ve come across pictures of celebrities or influencers wearing worn-out trainers as the latest fashion statement. Yes, we’re talking about the much loved, and equally hated, Golden Goose. Perhaps your first impression was one of bewilderment: How can such battered trainers be sold as new, and what’s worse, at a high price? Who would pay for that? Well, maybe now, having seen it so many times on people you follow and admire, your aversion is diminishing and you’re starting to contemplate buying them. After all, they are fashionable, aren’t they? But why does this trend glamourise poverty?

Beyond a question of taste, the rise of dirty trainers and torn jeans seems to be a symptom of a serious problem for society: the glamourisation of poverty. It is a subject of wide debate, which will raise many arguments for or against depending on the lens through which it is viewed. To really understand certain issues you will see below, you need to have an empathetic and open mind to put yourself in the other person’s shoes. In the end, our perceptions and experiences will shape our opinions, but they will not invalidate the feelings and realities of the other party. It is a delicate and complicated issue that we must open up to dialogue in order to be able to address it as a society in its entirety, without “sugar-coating” it.

The meaning of poverty

The problem, maybe, is that we do not understand poverty. Unless it is experienced first-hand, it is a situation alien to much of society. A reality that is often swept under the carpet in more developed countries. As if it only exists when it is talked about. A situation in which at least one billion people live in the world. It is not for nothing that its eradication is one of the 17 SDGs to be achieved.

For philosopher and anthropologist Francisco Checa, poverty is a concept that has changed with time and ways of life. In his article “Anthropological reflections for understanding poverty and human inequalities“, he indicates that, although the terms related to it have taken on different connotations – according to economic, social, political, military, moral or religious variables – they cannot be separated from difference, insufficiency or lack. Poverty, then, reflects, primarily, a state of lack of some good important to social and individual life, whatever its nature. And it considers hunger as the quality that determines it, whether it is physical hunger, social hunger, hunger for justice or freedom.

In the same way, he says that one is poor not only because of a lack of material goods, but also because of a lack of information and access to it, of education, of personal and social balance, of qualifications and so on. Thus, Checa sees poverty as a state of weakness, dependence, subordination, humiliation, contempt and deprivation of the means to achieve a humanly dignified life, with one’s primary needs satisfied. It is a constant struggle for survival whose gaps are marked by capitalism, which has created more poor people and widened the gap with the rich.

So, if poverty entails serious difficulties of inequality, hunger, misery, injustice and violence, why do we romanticise it? There are many opinions on the subject, but they all agree on the superficiality with which the problem is approached.

Through the prism of fashion

From grunge aesthetics, to normcore, heroin chic or homeless chic, fashion seems to be constantly inspired by poverty. But this is nothing new. Historically, the upper classes have been appropriating elements from the lower classes for centuries, turning the result of a necessity into a purely decorative object.

Historian Kimberly Christman-Campbell gives the example of Marie Antoinette, who used peasant aesthetics in an attempt to simplify her clothing. She even spent her days in a villa, created for her at Versailles, playing the role of a country woman. Of course, without the hardships and deprivations of those women. In the end, it was only a recreation; an idealised life, totally removed from reality, which ended when she wanted it to.

Something similar seems to be happening today with designs that imitate ordinary objects with ostentatious and expensive materials. Is this a critique or a mockery of disparity, or perhaps surreal humour or a homage to the everyday, Christman-Campbell’s text asks. And how should we take the consumption of these designs?

Many designers have produced collections that take poverty as an aesthetic element. Perhaps the best known case is the Golden Goose trainers, which we mentioned at the beginning. A brand that sells such footwear with a worn appearance for at least $500. Sneakers that are easily identifiable nowadays and that are quite popular, even being imitated by fast fashion brands. But it’s not the first and won’t be the last.

)

Haute couture houses have also fallen into this aesthetic. For example, John Galliano’s collection for Dior in 2000 is often considered the birthplace of homeless chic. Featuring torn garments and newspaper prints, the designer drew on the homeless people of Paris he observed while jogging. Similarly, in 2010, Vivianne Westwood presented overlapping garments, in her men’s collection, that simulated the way a homeless man dressed. Another design that caused a stir was Marc Jacobs’ bags for Louis Vuitton in 2006. These bags were worth thousands of euros, but they simulated bags with coloured lines, common in the markets. An aesthetic that Balenciaga also picked up, years later, with its Tati Bag, which imitated raffia bags.

Boasting of being controversial and irreverent, Balenciaga continued to bring out controversial pieces in different seasons and collections. From parkas that resemble the reflective coats of garbage collectors or street sweepers, to bags that replicate the rubbish bags that refugees use to carry their belongings. Even with models that simulate grabbing the most precious things as they flee. I wonder, are they trying to highlight a reality or is it rather a lack of sensitivity and relevance?

Far from being an occasional resort, designs in this style are perpetuated in the high-end market. Ralph Lauren makes his presence felt with a paint-stained denim jumpsuit that imitates a work outfit. Balenciaga repeats the dish, this time with a remarkably destroyed crewneck jumper. Nordstrom joins the trend by selling ‘mud-stained’ trousers. As if that wasn’t enough, a purse designed by George Sklecher has also been seen on the market, based on the shape of the disposable cups that beggars use to beg for alms in New York. It’s called Lucky Beggar. Tell me, isn’t that the best of puns?

The latest absurdity was perhaps that of Balenciaga in 2022, when it presented the Paris Fully Destroyed Sneakers. These trainers are a version of what Golden Goose has already capitalised on, but taken to the extreme. A shoe that is extremely dirty and worn out. Broken, practically destroyed, which went viral and generated great controversy as it cost thousands of dollars. The brand indicated that it is a design conceived to highlight the beauty of what is used, in line with its sustainability efforts. A shoe to be worn for a lifetime, as it is presented broken, it won’t matter how much wear and tear you give them. Marketing or mockery?

Is it a valid strategy? asks Karina Ortiz of Merca2.0. We will have to ask marketing experts if an unethical strategy can be considered acceptable. Does selling justify any action? Because, as they say, there is no such thing as bad publicity; the important thing is that they talk about you. Or is it ‘a criticism born from within the luxury industry’?

In either case, fashion is not the only industry that uses this resource. Poverty is exploited in many different scenarios, so many that they even go unnoticed.

Its use in other industries

According to María Laura Pardo, researcher and linguist, post-modernity has promoted the aestheticisation of critical issues and problems such as torture, dictatorship, the Holocaust or poverty; of the tragic, the violent and the horrific. But, “aestheticising poverty is much more than exhibiting photos, paintings or videos, it is generating a belief system that often creates stereotypes which, in a democratic and therefore egalitarian and just society, nevertheless tend to discriminate“. A view that could explain the massification and rise of trends associated with the aestheticisation of a social problem that does not seem to be diminishing.

For Carlos Ríos-Llamas, researcher and architect, this tendency can be observed in many areas, such as in urban renewal projects that paint houses in the poorest areas of the city with colours. It is not for nothing that he entitles his chapter “Aesthetics of misery: painting precarious urban areas with colours“, located in the multi-authored book “Places and identities: reflections on an imagined city”. On the one hand, he explains, there is the interest in generating tourist attractions. People are “attracted by the novelty of the abject“. On the other hand, there is the opportunity for place marketing: to commodify those spaces and integrate them into the city.

On television we also witness this propensity to sweeten poverty to serve as an accessory, incoherent to reality. It is common to see characters being portrayed as poor as a narrative device and only depicted in a certain way. No wonder they make us think that you can live a great life even if you don’t have much income. The real difficulties go unnoticed or ignored. A dream world, where the so-called ‘poor’ have spacious flats and opportunities in every corner, with dozens of shoes and perfect clothes for every occasion.

Yes, we know it’s fiction. But, as young Aaliya Weheliye rightly points out in the school newspaper The Evanstonian, “the media needs to do a better job of considering what poverty really looks like; it is not a peculiar personality trait, but rather a dangerous and frightening reality that many people face every day“.

Vilma Djala also sees how it is used on a daily basis. In her blog, TheContraryMary, she calls peasant food served in fancy restaurants, or cheap recipes prepared in fully equipped kitchens, inauthentic.

Poverty is exploited at every turn. It is used to increase the audience in programmes where presenters give away money or where they give away basic items (such as cookers or refrigerators) to poor people after meeting certain challenges. It relates this romanticisation to the bohemian style and the starving artist, as if this were necessary to create great works. They use the discourse of resilience and paint themselves as strugglers, when in reality they have not suffered any hardship: they have had private lessons, attended prestigious universities or travelled comfortably in different cities. This turns the discourse into a problematic where the rich appropriate the stories of the underprivileged.

Photography is no stranger to this problem either. In 2002, columnist Zoe Williams wrote an article for The Guardian following photographs by Miles Aldridge that portrayed the poor as fashionable subjects. Miles joined a wave of photographers and magazines that used the misfortunes of the poor as inspiration for clothing and interior design. It’s cool to look poor but not be poor.

Thus Zoe harshly criticised this current permeating today’s culture: “irony is the scoundrel’s way of evading moral responsibility. You can do anything, as long as it’s a joke, and you can’t object to anything on that basis, lest it be revealed that instead of a sense of humour you are hiding a leftist elf“. Even if the message is intended to be “witty and subversive“, by being aimed at a wealthy market – of certain characteristics and privileges – it loses its substance. “As a critique of consumerism, it is neutralised by its medium and ends up being perverse“, he says.

Williams also reflects on the attraction that poverty has for an outsider: it is something they cannot have. And that is the idea on which all these manifestations are based. Even religions have at their core the “idea that the poor are inherently pious“, that they enjoy a certain grace and nobility. An idea that carries over into creativity and art: “all the eras that prioritised creativity had consonant clichés about starving in garrets, as if starving would bring you closer to a higher sensibility“.

It is, then, a bias that has been tackled since antiquity to avoid addressing a social problem. A sad reminder of our inability to bridge gaps and one that we continue to perpetuate to this day. “This may have started as a grand conspiracy of the rich to keep the poor in their place by patronisingly praising their authenticity, but it has become a great enigma“, he notes.

Capitalism has accentuated power differentials, making it difficult to overcome socio-economic barriers. The structures that generate impoverishment remain in place. The system continues without noticeable improvements. So why the fascination with the lives of the less fortunate, why do we introduce common items as luxury goods?

Some theories about the phenomenon

The misfortune and hardship suffered by millions of people becomes cool. Perhaps innocently, perhaps not. A simple life is idealised, but made as a representation of reality. It is not the same to have a kitchen with a vintage aesthetic as to have one that is really from the 60s because you can’t afford to pay for a new one. Maybe it’s like watching a painting or a play; you don’t become part of it, you don’t become part of the daily experiences and suffering. It’s just another activity.

Donald Macaskill, in his reflective article on the glorification of poverty, expresses his concern about this situation: are we aware of the effects of the acceptability of poverty? There is a delicate balance between stigmatising it and romanticising or validating it, says Macaskill. He is blunt in his view that this glorification is “a perversion of painful reality“. Moreover, he points to the hypocrisy of poverty in this discourse, where it is taken as a source of inspiration, idea or design. You see what you want to see, what is convenient to see. There is no real commitment in those who pretend to be part of the oppressed in order to project some quality, such as nobility or honour, attached to the idea of a simple life.

“When art and fashion turn poverty into a new aesthetic for clothing or interior design; when philosophies and belief systems elevate the poor to the status of especially worthy beings; or when creativity and genius are presented as the fruit of suffering and economic need, we have perversely lost our moral compass“, he continues. “Do not be fooled into thinking that poverty is romantic, glamorous or inevitable (…) those who live and have known poverty know that it is an experience and a pain that ultimately does not merit art or creativity, design or aesthetics, but demands action, solidarity, reorientation and change (…) The air of poverty is too raw to breathe or glorify“.

Thus, the romanticisation of a harsh reality turns the problematic into a superficial idea, removed from any negative connotation. And, its constant presence in our daily lives renders us insensitive to it. It limits us to seeing poverty as something aesthetic or as an experiential experience/activity that we choose for a moment, and not as a constant that remains for generations for a large part of the population.

For Vicco García, journalist for Marie Claire, glamorising social phenomena “is nothing more than a demonstration of how the upper classes often demonstrate their power by appropriating an element, reformulating it and using it without impunity; without taking into account that this may be the reality of a more disadvantaged social class“. A tendency that is not new and, as we have seen, has been present since time immemorial. The privileged social classes take styles or elements from the more popular, poorer classes. “They make fashionable what for others is a misfortune and which also excludes them from society“, says García.

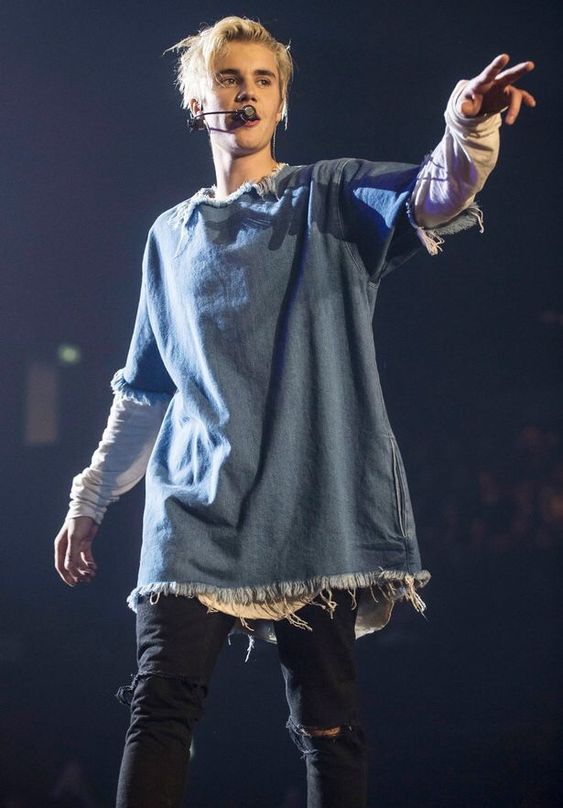

Why is it acceptable, or even chic, for certain classes to dress in such and such a way, while others are vilified for wearing similar garments? The factor, when not, seems to be money. It is common to see celebrities wearing tracksuits or oversized clothes. We label a celebrity’s faded or hollowed-out clothes as good style, but why do we look down on someone from a lower social stratum when they wear them?

It is the “hypocrisy of a world where financial stability determines one’s acceptability“, says Carol Davis, editor of the Columbia Political Review, the university’s journal. A cynicism that lies in the idea that this style is acceptable to the rich, but unacceptable to the poor. The rich choose this appearance of intentional poverty-based attrition. It is one more way of showing their wealthy status, their conspicuous consumption. They can afford to pay large amounts of money for torn jeans or clothes that appear to be covered in mud; while there are people who cannot afford to buy a new one. It therefore “perpetuates yet another barrier in public perception between rich and poor“, Davis notes.

This attempt to simulate poverty leads brands to engage in irony and mockery when confronted with the tragic reality. However, some brands use these characteristics to form a highly identifiable and easily recognisable element among their users and followers.

Brands and the falsity of their narrative

There is a fine line between inspiration and appropriation. A line that brands seem to be unaware of, of blurred boundaries that tend to constantly move, making them commit insufferable blunders, even if they sometimes get away with it. Being such a controversial topic, what drives brands to revert to poverty as just another aesthetic to be used by the rich?

It is a phenomenon “that looks at the world with a purely visual eye and refuses to consider meaning“, writes Leeann Duggan in her article for Refinery29. An aestheticisation that invisibilises latent problems in society and fails to achieve awareness and real change, even if the intention was to engage its audience in another reality. Duggan talks about there being a human disconnection when looking at another human being, under a privileged lens, as a source of style or inspiration. A being with basic needs, inhabiting a world whose truth is far from ornamental, “who rather than being inspirational need consideration“.

Just as it has served favourably as a symbol for certain brands, it has all the power to dent the reputation of others. A double-edged sword, on which brands seem to gamble in order to provoke reactions – positive or negative – in their consumers. As if it were a game, they begin to adopt an aesthetic that is far removed from their reality. And, they use these elements as an emblem of rebellion, non-conformity or authenticity. The falsity of the discourse lies in a null link with these sources. A disguise that hides a “layer of plausible deniability by calling it satire“, adds Zeeshan Khan from The A-line Magazine.

Even if it is an attempt by the brand to convey authenticity, replicating the appearance of disadvantaged people falls into an aestheticisation of their hardship. There is “something inherently classist in this fetishisation of decadence“, notes Gaby del Valle in Vox. Which is not hard to understand if you look at the use of the precarious chic style: you wear it because you want to, not because you have to. It is a choice. One that, no matter what the intention, backfires.

Rich people who don’t want to look rich

Culture, elites and brands have been adopting this trend for decades, shifting the focus from the real problem to an aesthetic issue. It is not surprising that today we wear garments, so deeply rooted in the way we dress, whose origins we do not know. We forget that the real cradle of pieces like ripped jeans or oversized T-shirts can be found in places as obscure as poverty.

Nor is it strange to see politicians trying to win the affection of the people, going to markets to have breakfast, trying to be one of them. Populism thus becomes a tool to get the vote. An element of artificiality that seeks to generate empathy and reinforces the line that it is not only acceptable to pretend to be poor, but that it can bring results. It is not for nothing that multimillionaire businessmen have taken advantage of this resource to sit in the municipal, congressional and even presidential seats.

So this is a real problem; a long-standing dissonance. If we spoke earlier of Marie Antoinette as an example, this has not been an isolated occurrence. Throughout history, the rich have dressed casually during periods of inequality in an unfortunate attempt to blend in with the crowd. Perhaps aware of their privilege, they try to manufacture a disguise of authenticity that brings them closer to the masses. They do not want to be demonised for the facilities they were born with. But this role-playing diverts attention away from what really matters: the setbacks of a system that perpetuates poverty. Jocelyn Figueroa, for InvisiblePeople, puts it this way: “the more we admire pain and suffering, the further we are from putting an end to it“. By romanticising a reality we disconnect it even more from its harshness.

A cynical populism, Christman-Campbell calls it, where the rich masquerade as the poor and there is no real concern to change things or seek solutions. Where irony is used to dress like a worker, but without having to work like one. And where the main economic beneficiaries of these trends are the millionaire families who run such brands.

We see it in Silicon Valley, with boardroom executives dressed casually. An aesthetic expanded, perhaps by Jobs or Zuckerberg, that has given rise to a new uniform: that of the ordinary, casual, unpretentious worker. However, Christman-Campbell points out, the reality is that their clothes are anything but ordinary. Are they designer T-shirts or trousers priced easily over a thousand dollars – is this a criticism or a mockery of disparity, she wonders. We see it, too, in celebrities who wear flannel shirts and caps reminiscent of lumberjack or trucker clothing; or in teenagers who embrace this aesthetic as a symbol of youth, rebellion or nonconformity, to separate themselves from their parents’ generation associated with tradition, antiquity and ostentation.

Victor Lenore of Vozpopulí sheds some light on this development. He argues that the international upper classes need a splash of authenticity; a brief sojourn out of their world. “They need occasional contact with neighbourhood life in order to feel dangerous and gain street credibility”. They enjoy contact with the excluded, he points out. As if it were a simple experience, the rich immerse themselves in a superficial projection of a reality that hides serious difficulties. “This aestheticisation of poverty serves the interests of those at the top, but trivialises the suffering of those at the bottom“, she says.

Kat George, on the other hand, believes that humility is the main factor why the rich aspire to appear poor. Why? Because the romanticisation of poverty projects an aura of purity onto the poor that the rich can’t buy, and exonerates them of any guilt. So, in an attempt to achieve this grace, they “avoid the dignifiers of their economic position“.

They are not trying to get rid of their wealth, but to console themselves with the internal – and eternal – weight of the guilt of their privilege. An attempt at humility. But, George argues, “for the rich to pretend to be poor is neither imitation nor flattery”. In fact, it is romanticising “an everyday reality for many, often born out of cyclical patterns of institutional bias, social stigma, cultural abuse and a whole system that is rigged to ensure that the poor remain poor, while the rich jealously guard their privilege“.

Moreover, George reiterates that, in trying to appear as ordinary, genuine and empathetic people, they fall back on a misguided discourse that appropriates visual resources from a constant struggle that lies in the midst of “socio-economic barriers’ that ‘cannot be dismantled“. A discourse where poverty is seen as a choice or option; where some are celebrated and others belittled, by wearing certain things. In the end, a poor person will still be examined negatively, while a rich person acting poor will be praised as subversive or non-conformist. An aesthetic that “denotes that those who create these trends and those who follow them have never had to endure any kind of palpable struggle“, he says.

An increasingly polarised society

At a time when social differences are glaring, where economic problems abound around the world, and where the culture of cancellation lurks, why do we not hesitate to buy old clothes?

Christman-Campbell reflects on whether this is a symptom or a cause of discontent? Today, sensibilities are more volatile than ever. Scrutiny haunts us through social media, on the lookout for any slip-up worthy of public humiliation. Widening gaps have made it “politically incorrect to flaunt one’s wealth“.

So, if poverty-inspired elements have been around for decades, what has changed: have we become even more desensitised to human misfortune to capitalise on its aesthetics?

Designers defend their work as social commentary. Consumers, unaware of the waste, defend quality and novelty as price support, without realising the root of the problem. The historian offers one possible support: the indicators of luxury and authenticity are changing with increasing speed. She observes that there used to be a clear distinction between work, home and gym clothes. Today the paths are blending. Similarly, dressing well has never been easier and cheaper. This leads the rich to look for ways to distinguish themselves, for when “a fashion becomes popular, it can no longer be called fashion“. Thus, the rich are balancing on a dangerous game; one that has authenticity and ostentation as two sides of the same coin. Careful how you toss it; lest it land on the wrong side, at the wrong time.

As you have seen, the issue goes beyond the appearance of a product. It is an issue that invisibilises latent problems in society, and which we only perceive when a cognitive dissonance arises: a nonsense that leads us to question the motive of a design (such as the extremely worn appearance of Balenciaga trainers).

Sara Moniuszko of The Colombus Dispatch suggests that this discordance occurs when they assume identities that do not belong to them; when they merely mimic a style without conveying a real message. In such a case, why do “stars and brands engage in a style that is so far removed” from their reality, she asks.

The main reason, he says, is the yearning for identification. For example, celebrities seek to get closer to their fans. “They try to appear as if they never had privileges in order to create that relationship with their millions of fans in a direct way. It is an effort to humanise themselves, to seek empathy and belonging in the masses, to ‘not dress like you’re above them“. They may join in without intending to offend, but in doing so, in one way or another, they dilute “our ability to see such a community“. A misguided move, which does not delve into the real dilemma of his muse.

The superficiality with which aesthetics is approached is detrimental to the art perspective of finding beauty everywhere. The charm of the ordinary, of broken or dirty things, remains trivial, frivolous and empty, when reality is marked by class division. Moniuszko warns: “Be careful not to erase people who are having a hard time, in the process of seeing beauty in destruction“.

Whether an act guided by naivety or ignorance, or a decision intended as provocation; the glamorisation (a.k.a. idealisation, aestheticisation, romanticisation) of poverty is an issue far from over. Subject to debate, it is certain that in the years to come we will continue to talk about this or that designer who markets from controversy. What is outrage for some will be satire for others. I only hope, sincerely, that the continuity of such aesthetics does not signify the decline of society; nor does it equate to disinterest or indifference towards our own species.

What do you think? Share your opinion in the comments. Let’s start the dialogue.

You may also be interested in: The hidden reality of tourism: animal exploitation.