‘The world’s richest 1% bag nearly twice as much wealth as the rest of world put together over the past two years’ reads a shocking Oxfam press release. It has published its ‘Survival of the Richest’ report back in January this year. Alarmingly, the report revealed that the richest 1% of the world’s population had obtained almost two thirds of all new wealth ($42 trillion) created since 2020, twice as much as the bottom 99%.

Astonishing facts like this constantly reinforce that, as the rich become richer, the income gap between the wealthiest and poorest in the world is only getting more pronounced. Undoubtedly philanthropy is a powerful force for good. But systems ultimately need to be established to give people in poverty access to the financial tools through which they can build their own future. For that reason, financial institutions have a crucial role to play if we are going to begin to bridge this gap.

A solid foundation would be to achieve financial inclusion. It would mean access for all individuals and businesses to useful and affordable financial products and services. Yet as it stands, financial inclusion is far from a reality. It was estimated that around 1.7 billion adults lacked a bank account in 2018 (according to the World Bank). A significant number of these were women and people in poorer rural areas. Microcredit, among other tools, is an innovative way to begin to provide this access.

Microcredit as a way forward

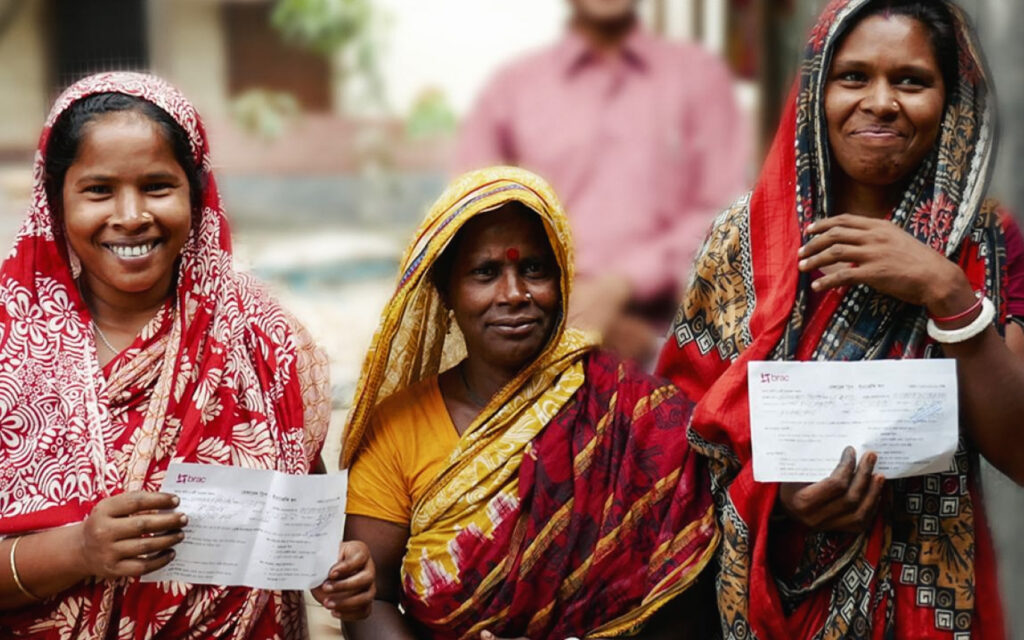

Motivated by the devastating famine that hit Bangladesh in 1974 and the harsh money lending operations taking place in the rural villages of the country at the time, economist Muhammad Yunus pioneered the concept of microcredit. In its simplest terms, microcredit is a form of microfinance. It involves an individual taking out a very small loan, with easy conditions, to help them set up a business. Low-income rural villagers often have no way of affordably getting transport to a conventional bank and, if they did manage such a feat, they would likely be sent back to where they came from empty handed. Recognising this, Yunus began by lending US$27 to a group of women from the village of Jobra from his own pocket.

The stringent nature of most traditional banks means that they are highly unlikely to lend money to anyone who is unable to offer some form of security in return. In other words – they won’t lend to some of the most vulnerable people in the world. According to Yunus, conventional banks fundamentally treat poorer people as though they aren’t creditworthy when, in fact, poor people (and poor women in particular) can be highly creditworthy but simply don’t have access to the correct financial services.

With the $27, the women each bought the materials needed to make bamboo stools which, in turn, they would sell. All the borrowers successfully repaid Yunus and their businesses began to sustain themselves. Simply having access to the correct financial resources empowered them to become entrepreneurs. In most cases it added a valuable second income stream to their household. So, having seen first-hand the exclusivity of the conventional financial system and the success of his own trust-based method of lending, Yunus set up Grameen Bank in 1983.

Grameen Bank

Since 1983, Grameen Bank’s customers have been taking out microloans at an average of around $100 per loan. They use these loans to purchase the materials necessary to set up businesses. Unlike conventional banks, Grameen Bank operates on trust. Given that collateral is not an option for those in extreme poverty, the lenders tend to pool together a group of borrowers. Success therefore depends on all of the borrowers’ contributions. Grameen Bank takes its services to its client’s doorstep.

All banking transactions (excluding loan disbursement) take place at the village level centres. The centre managers organise them and they help to support the women, ensuring that they are on the right track with their finances. This training and mentorship is crucial to the whole system. And, as it turns out, poorer people can be trusted to repay their loans at a much higher rate than most rich borrowers. Between 1983 and 2009, the bank lent more than $8bn to nearly 8 million people in

Bangladesh who had a 98% repayment rate.

The future of lending

Over the past three decades, microcredit has spread to all corners of the globe. In Europe, however, the practice of microfinance is still very much nascent.

While microcredit is not necessarily the only solution, it proves a fantastic way to support entrepreneurship and lift people out of poverty. In providing a person with financial access, you also provide them with confidence, self-belief, and entry to a previously inaccessible economic system.